INTRO:

It is not very often that game developers would dare to design a 4X title with real-time gameplay. The calculations that are needed to keep track of so many variables can be a considerable load on CPU resources. However, Paradox Interactive had achieved just that with its seminal Europa Universalis IP, and has gone to achieve so much more. Yet, conspicuously, it did not make a move into the sci-fi sub-genre of 4X games until much later.

Stellaris is the result of that move. Debuting in 2016, it has since benefited from continued attention from its developers, undergoing one major revamping and much, much fine-tuning amid plenty of feedback from fans who believe in the game. It has not had any reliable competitor in the same niche of real-time 4X games, at least not any with a profile as high as it has.

(Arcen Games’ The Last Federation is the closest to it, but it is a really a different cup of tea.)

PREMISE:

Any sapient species would eventually wonder what is out there, even if it could not reach it. Yet, like any sapient species would, it would eventually figure out a means for getting there. Of course, getting there. and knowing what is out there, are two very different things.

The player takes on the near-omniscient role of being the entirety of a civilization of sapients, starting out with a plan to colonize the stars and eventually exploring the rest of the galaxy. Along the way, depending on whatever content pack and playthrough conditions that the player has chosen, the player’s civilization would discover other civilizations, as well as secrets that are tucked away in nooks and crannies of the galaxy, and sometimes beyond.

Dealing with other civilizations and the secrets of the galaxy will be the overarching themes of any playthrough, because there is so much variety that the player can expect. Ultimately though, the player’s goal is to become the dominant civilization in the galaxy, through a range of means that includes diplomacy, scientific advancements and, of course, war.

PLAYTHROUGH CONDITIONS:

Perhaps the most important factors of the gameplay are those that the player set before the start of any playthrough. These are even more important than the traits that the player would pick for his/her civilization. This is because these factors affect the experience of the playthrough.

Pick wrongly, and the player might have experiences that would discourage any further interest. This can be a terribly unpleasant struggle against enemies that are already overwhelmingly powerful from the start, or the player’s civilization would eventually run out of challenges to overcome and become all but alone when they stay at the top of the pecking order for too long.

The problem with this aspect of the gameplay is that there are many variables to consider – too many for anyone that is not already a meticulous pedant. Furthermore, as the game gets more content from its expansion packs, more and more of these variables interact with each other in significant ways that a new player might not be able to readily extrapolate.

Fortunately, there are pre-sets that are different enough to result in different experiences, if the player does not want to spend too much time deliberating over the variables.

TUTORIALS:

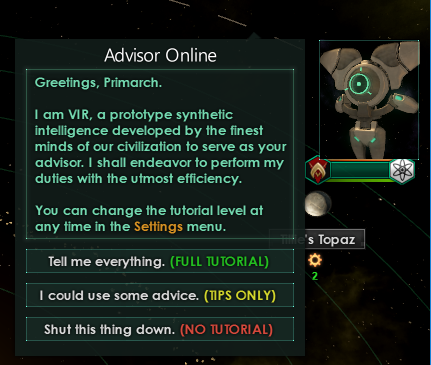

The game can be dauntingly complex, so there is a set of tutorials for the player to follow. The keyword here is “follow”; the tutorials are not the hand-holding kind, for better or worse.

Most importantly, the tutorials only teach the basics, and only impart advice that is applicable to any playthrough, regardless of the nuances in the gameplay.

PAUSING AND GAME SPEEDS:

Stellaris may run in real-time, but being a 4X title, keeping up with the gameplay second by second can be daunting. There are also many advanced strategies that require impeccable timing. Therefore, the player can choose to pause the game at any time to think on some decisions or to check things. Alternatively, the player could slow down the game, just for scenarios where split-second timing is important. The player can also accelerate the gameplay speed, just to fast-forward through lulls in the playthrough.

MONTHS, DAYS AND YEARS:

At the default game speed, each second in real-life generally equates to one day in-game. However, the actual time elapsed may be different according to how much processing load is being placed on the CPU.

Days are usually used for things with short durations, such as the repair timers for starbases (more on this later). However, there are occasions where timers have four-digit counts in days.

Nothing in the gameplay uses weeks as a basis, but some of them use months. The system of months appears to be almost entirely based on the real-world Gregorian calendar, so there are months with 31 days and other months with 30 days. Every month, a civilization gets its income of resources, and its scientific research advances (more on these later).

PLAYER’S CIVILIZATION:

Most other 4X sci-fi games limit the scope of their content by establishing a series of canonical species while allowing the use of these as templates for custom-made civilizations. Stellaris has no canonical species, but it does have many pre-sets for the player to choose from, or edit as he/she likes by removing or adding traits.

PHYSIOLOGY DOES NOT MATTER MUCH:

The physiology of any species is relegated to mostly a cosmetic option. In fact, Paradox has released several packages of cosmetic content; this will be described later.

Other than its preferred climate, the only other part of a species’ physiology that has an effect on gameplay is the phenotype of the species. (Phenotypes are the general appearance of life-forms.) Generally, species of the same phenotypes are better disposed towards other species of the same phenotype in matters of diplomacy, though this is just a small variable. (Specifically, it alters the Xenophile or Xenophobe modifiers; otherwise it does nothing else.)

This can give a bad first impression of the game’s complexity, especially if the player is a long-time follower of 4X sci-fi games that are species-oriented. Furthermore, considering that contemporaries such as Amplitude Studios’ Endless Space has made a name for itself by focusing on the capabilities of each major species, there is the impression that Paradox might have lost an opportunity to make some trademarks of its own.

That is not to say that Paradox has not invested effort into making some species recognizable as something canonical. There are a few of these, but they are reserved for the “end-game” content, which will be described later.

MUTABLE CIVILIZATIONS:

Having mentioned that physiologies of its original species do not matter, the things that matter more to a civilization are how it is organized and its culture. There are many variables in such matters, but as a general rule of thumb, they are all changeable. (Expansions would later introduce “civilizations” that have fixed “cultures”, for better or worse.)

These changes can occur through either the decisions of the civilization’s leadership (the player’s decisions, in the case of the player’s own civilization) or the actions of others. There are means to force or subvert another civilization to take on different forms of organization and/or different cultures, which will be described later.

There are three factors that determine the organization and culture of a civilization: Governing Ethics, Civics and Authority. All three will be described in their own sections, but it should be said now that none of them are set in stone. They can change during the course of a playthrough, mainly through the player’s decisions, but there are factors that are not within the player’s control (especially if the player had been playing poorly).

GOVERNING ETHICS:

The player starts a playthrough by picking the Ethics of the government of his/her civilization. The Ethics of the government are the main factor in determining how much control that the player has over the policies of his/her civilization. They also determine the response of other civilizations to his/her civilization.

Interestingly, the populations within a civilization may have ethics that are different from those espoused by the government of a civilization. This contributes to the system of factions, which will be described much later in this review article.

The player does not suffer a game-over if the ethics that he/she has chosen for the government before the start of a playthrough are forced to change beyond his/her control, but he/she would have to deal with policies that he/she might not want for his/her preferred playstyle. Of course, he/she can always make decisions that eventually push his/her civilization back to the ways that he/she wants.

More importantly, changes in ethics will not alter the player’s control over the most basic and fundamental of decision-making in 4X games, such as deciding what buildings to build on a planet and which ships to build and how many.

Some very important ethics will be described before Civics and Authorities.

AUTHORITARIAN VS EGALITARIAN:

Authoritarian governments have a lot more leeway in implementing policies and even repealing them on a whim. This includes implementing harsh policies like slavery; indeed, slavery can only be implemented in authoritarian regimes. On the other hand, authoritarian regimes are resented by everyone except other authoritarian regimes.

Egalitarian governments insist on having decent living standards for everyone, which means that every population unit has a drain on resources, namely Minerals. However, paradoxically, such governments also have blanket percentage-based reductions on this drain (which is called “Consumer Goods” in-game). Egalitarian governments obviously do not have access to the slavery system, which means that they cannot exchange the happiness of their people for short-term gains (or long-term ones, if the player could keep unrest among slaves at a manageable level).

XENOPHILIA, XENOPHOBIA & SPECIES AMBIVALENCE:

The next set of important ethics are those that determine the presence of sapient species in a civilization.

A civilization could try to pursue the genre’s tradition of single-species civilizations (like those in Stardock’s Galactic Civilizations), which means that it is likely to have the Xenophobe ethic. However, having such an ethic would immediately put them at odds with just about any other civilization, especially xenophiliac ones.

Conversely, a civilization might be xenophiliac, ever eager to add new species to its diversity, for all kinds of reasons including wanton and whimsical ones. These civilizations are hated by the xenophobic ones, but they do not incur a flat-out dislike from the others – the other traits of their civilizations notwithstanding. Furthermore, having other species come into a civilization pose as many problems as opportunities, some of which will be described later.

Of course, a civilization could just opt for a species-neutral ethic (i.e. not having the Xenophile or Xenophobe ethics). However, the civilization will have to contend with species coming and going into the civilization; the measures that the civilization’s leadership (that includes the player) would take to “solve” these issues will colour the opinions of the citizens (through the system of factions, which will be described later). This may push the people of the civilization towards xenophilia or xenophobia; balancing these tendencies is an incredibly tricky act.

Such gameplay experience lends to a lot of role-playing opportunities, if the player is the kind that wants to include any role-playing moment whenever possible.

FAITH AND MATERIALISM:

For better or worse, religiousness and materialism are mutually exclusive ethics. This will decide how the player fares in managing the economy of his/her civilization, and its long-term growth beyond matters of the bottom-line. Spiritualist civilizations have a much easier time controlling the ethos of the people and advancing in the Unity system (more on this later), but Materialist civilizations have an easier time expanding their economies in the long-term because of their acceptance of technologies considered heretical by their antitheses.

START SOMEWHERE IN THE MIDDLE OF THE ROAD:

For better worse, the player must pick Ethics, Civics and Authorities before the start of a playthrough. There is no option to create a civilization that is somehow completely ambivalent to everything.

The player can still try to start close to the middle of the road, if he/she so wishes - probably after deciding that the benefits of the extremes are not worth their setbacks. However, such playthroughs are – perhaps ironically – fraught with the most troubles. This is because the people of the player’s civilization might not see things their government’s way.

CIVICS:

Civics are additional characteristics that complement the Ethics, and are often the things that would define the player’s gameplay experience (unless they are changed, for whatever reason). In fact, some Civics are not available unless the player picked specific Ethics and, sometimes, at specific levels of Ethics.

Some of these civics, especially the ones that can be taken by any civilization without any pre-requisites, are just straight-up empire-wide bonuses – something that long-time followers of the space sci-fi 4X genre would be quite familiar with.

Some others though, can greatly affect the gameplay experience. Incidentally, these civics cannot be changed at all during a playthrough, barring significant events in which their pre-requisites are nullified. For example, civilizations that have Inward Perfection are isolationists that cannot have any interactions with other civilizations or even other species at all, but are compensated with benefits that make them quite self-sufficient.

The only way to “change” these civics is to make the civilization fail to meet their pre-requisites. Returning to the example of Inward Perfection, this civic can be disabled by forcing a civilization to be no longer Pacifistic or Xenophobic. This civic does not go away, however, and can be reactivated again as soon as the pre-requisites are met again.

AUTHORITIES:

The final character of a civilization is the type of its government. There are four base forms of government: Imperial, Dictatorial, Oligarchic and Democratic.

Oligarchies and Democracies are the only ones where elections are held, more so for Democracies. The main differences are how long the elected rulers get to stay in office, and how much control that the player has over who gets elected (if he/she has no qualms about meddling in fictional elections). The latter is important, because rulers come with agendas, and in the case of democratically elected rulers, they come with mandates too. These will be described – and bemoaned – later.

Obviously, Imperial and Dictatorial civilizations have supreme rulers for life. These are desirable to a player if he/she wants to maintain very specific agendas to fit his/her playstyle, at least until the ruler dies.

A civilization is given a name and lore description depending on the permutation of civics and authority that it has, but this is just a cosmetic trait.

SPECIES TRAITS:

Stellaris does allow civilizations to eventually have many species, but the premise of the game means that every civilization only ever starts with just one, specifically the one that has risen to dominance over their homeworld.

The player is given a few points to spend on species traits with varying costs in points, and the player can only pick up to five traits – good or bad. The player can at least get one good trait for the species, but any more very likely will require the selection of bad traits, which grant more points to select good ones. The player could opt to just pick good traits of course, but the player’s species is likely to never come across situations where they would greatly excel at something.

Species traits can be altered later, after a civilization has obtained the necessary technologies. However, this is not a matter that is as simple as swapping variables. This takes time, because the changes have to be implemented across selected population units. More importantly, this takes up resources that could have been spent on Societal research; this will be described further later.

SPECIES RIGHTS:

Then, there are rights for species. This system was introduced to make handling population units more complex yet simpler at the same time; examples of either extremes are mentioned later, where relevant.

There are many types of rights that a species (organic or non-organic) can have. Each type of rights has something to do with other gameplay systems in the game, especially those that concern population units. These rights will be mentioned later where relevant, but it should suffice to say for now that the player should make his/her decisions wisely, because species rights are a subset of the overarching system of policies, which will be described later.

That said, one of the important types of rights is citizenship status, or lack thereof. Full citizenship affords a species all of the fundamentals for a decent living; anything less makes them vulnerable to exploitation and oppression. (Indeed, a workable playstyle with exploitation and oppression can be achieved, if the player can manage the risks.)

Specific population units of the same species or sub-species cannot be given different rights; the game does not provide this versatility, apparently due to a decision on the developers’ part after observing how cunning players exploited the previous incarnations of the system for some overpowered playstyles. Blanket species- or sub-species-wide decisions have to be made, for better or worse.

POPULATION UNITS:

The people(s) in a civilization are quantified according to “pops”, which is the game’s term for groups of people; the in-game advisor even utters the word. Each group of people can be directed to do the same thing, namely sitting on and working on a tile. In this review article, the longer term “population unit” would be used, if only because “pop” sounds terribly awkward to me.

Anyway, the player starts with a few population units. In the case of people from organic species, new population units seem to spontaneously grow on any tile that is not already occupied by any population unit; the game explains this as internal migration, natural births and cloning (when the tech becomes available). If there are population units of different species or sub-species, there will be one growing population unit for each of them. The ramifications of this will be described shortly.

If the civilization purges a species, any population unit that appears later in the civilization will never be of the purged species. However, that species will still be in the civilization’s list of species, albeit as an undesirable.

POPULATION GROWTH:

A population unit that has just appeared will not be fully usable, initially. The population unit has a meter that shows how close it is to achieving maturity.

In the case of population units from organic species, the time that is needed to reach maturity depends on the number of population units that have been around on the planet; having more of them already around makes the maturity take longer to happen.

This runs counter to logic, since population growth should be proportional to the level of existing populations. Of course, this is a computer game thing, specifically something about gameplay balance.

There are other factors, such as any Civics or Traditions (more on these later) that provide bonuses to the speed of growth. These are much more reliable factors of growth than anything else.

Any surplus food that the civilization is making contributes to the growth of organic population units. However, the bonus is rather small. Considering that each population unit consumes 1 unit of food each month (more on food later), that each 1 surplus unit only produces a 1% increase over the default growth rate is rather disappointing.

Perhaps the most important factors in the creation of new population units are the numbers of species and planets that the player’s civilization has. Each planet can support the creation of one population unit of each species or sub-species that is allowed to multiply, so having more planets means that the civilization’s overall population levels can rise quicker.

Yet, a population unit of any species or sub-species can only be created by having at least one empty tile. This means that if the player wants to have each planet continue to contribute to the growth of the civilization, one tile would have to remain undeveloped on each planet. This can seem silly.

In addition, if there are multiple growing population units (all of whom would be of different species or sub-species) on a planet, the planet’s conferred growth rate is split between them. Generally, the species with highest proportion of total population on a planet gets the lion’s share, so its population units grow the fastest if there are more than one around. The other population units continue to hog their tiles while they mature much more slowly.

Growing population units cannot be destroyed, short of declaring that their species or sub-species are to be purged. They cannot be resettled to other planets either.

With all of these factors to keep in mind, managing the growth of population units of one species is already daunting enough; having to manage growth of multiple species or sub-species is even more complicated.

The player could choose to stop a specific species from being able to make new population units. This, of course, displeases them (quite greatly, in fact). However, they get to maintain their population units and remain productive.

MIGRATION:

If a civilization has enabled full migration rights for an extant species in the galaxy, a population unit of that species can choose to just move out to another planet in the same civilization, or another civilization that welcomes migrants of that species. The reasons for population units wanting to migrate are opaque, unfortunately.

There have been some observations made by players, of course. For example, migrating population units often follow progressive factions (more on these later) and they often come from planets with bad conditions (e.g. low habitability). The player can observe such examples when the player conquers a planet that has population units that are ill-suited to the world that they are on. (This can happen when CPU-controlled governments make some poor decisions; this will be lamented further later.)

Anyway, the main reason that the player might want to dabble in migration is that the player might have a lucrative planet that can be colonized, but does not have the correct species for its clime and does not want to subject the planet to terraforming (which take a long time). Getting into a migration agreement with another friendly civilization that has the species that the player wants can be helpful.

Unfortunately, again, the game does not inform the player about the factors that encourage migration. The rights of the migrant species are likely to be important, but not a guarantee. In one instance, I have set favourable conditions for multiple species but found that only one population unit of them took the proverbial carrot. In another instance (made through some save-scumming), all of the foreign species took the carrot and they came in droves.

There are buildings that encourage migration to the planet that they are on, but sometimes they do not seem to do much either. Perhaps the other civilizations have forbidden their species to migrate, but the player is not able to see whether this is so. (The player can certainly prevent the species of his/her own civilization from migrating.)

A population unit that wants to migrate has a label that shows that it is going to migrate, often after several months. However, this is not a guarantee; every month, they might change their mind, for whatever reason. (There are some observable reasons, such as more tiles being opened up on the planet that they are on.)

Furthermore, the migrants might not make the best choices, due to possible uses of fickle RNGs in their decision-making. For example, a population unit of a species that prefer tundra worlds might migrate to a desert world. (There will be more on planet habitability later.)

A migrant population unit effectively becomes like any other population unit, albeit with a short-term happiness bonus. It can be shuffled from tile to tile, or resettled in another world if the player wishes it (and it would retain the bonus anyway).

Overall, the migration system is unreliable in getting population units of other species, no thanks to how incomprehensible the factors of migration are. Unfortunately, migration is an issue that matters to one of the factions in the faction system, which will be described later.

DROIDS/ROBOTS/SYNTHETICS:

Eventually, a civilization gains the ability to build population units that are composed of semi-autonomous machines. They start their existence in servitude to the species that created them, and they tend to be incapable of anything other than working on mineral and energy production until they become more sophisticated. Indeed, there are three levels of sophistication to them, depending on the techs that have been developed for them: the simpleton robots, the slightly less clumsy droids and the fully realized synthetics.

When they are merely robots and droids, they do not have any happiness ratings whatsoever and have no issues with servitude. Once they are synthetics, however, they eventually gain sapience and have happiness ratings. This is a watershed moment for the player’s civilization, because the player will need to decide on what to do with them now that they are well aware that an existence of servitude is very dissatisfying. (The Synthetic Dawn DLC makes this event even more destabilizing – but that’s for another review article.) Granting them full citizenship makes them happy, but angers any spiritualist faction outright. (The irony is that machine population units can join spiritualist factions too.)

One reason to have population units of machines – sapient or otherwise – is that the habitability of planets is a non-issue. However, they do not gain any bonuses from being in the correct climate either. Another reason is that they are immune to diseases, if there are random outbreaks of plague.

However, perhaps the greatest reason to have them is that their population level can be controlled. On the other hand, their proliferation is slow and costly. Only one population unit of machines can be built on any planet at any time, and they have a building rate that can be improved with only a few ways. They also cost minerals to make, which complicate resource management. They may not need food, but they require Energy for maintenance instead.

SUB-SPECIES:

Every species starts with its original strain. More strains can be obtained when the player’s civilization comes across the means of genetic modification, but there may also be special events where the player is given the choice of creating a different strain. Of course, such events come with a price, namely societal upheaval about having “mutants” among the people.

SUB-SPECIES TEMPLATES:

Only new sub-species can be made; designing entirely new species is not possible during a playthrough, even with the Utopia DLC. A new sub-species will always be associated with its parent species.

The only exception to this is when a civilization gains machine population units for the first time, typically after gaining the tech for Robots. The civilization’s leadership is given the choice to design a machine “species” from scratch.

Nevertheless, the main limit on traits still applies: five regular traits of any kind and in any mix.

OTHER EXTANT SPECIES:

A civilization may allow migrations of species with other civilizations through agreements. A civilization might allow refugees to settle. A civilization might even defeat another civilization and gain their planets, as well as their populations from different species.

Together with the proliferation of sub-species, a civilization’s government will eventually have to decide how to manage the gamut of peoples.

The beneficent but not always wise decision is to grant them full citizenship, effectively turning a civilization into a multi-species civilization. However, the other species, especially those from defeated civilizations, may carry baggage, such as bad traits and factional allegiances that are just against the current government of the day. The government can choose to purge them, but this comes with its own problems, not least of which is revolt.

It is a balancing game that can be daunting to deal with, but it is manageable and can provide rewards in the form of convenience. For example, being able to colonize planets with different climes is a considerable advantage over civilizations that have to terraform planets, if they bother at all.

SLAVERY & SERVITUDE:

Of course, there is the darker but more gratuitous decision that is enslavement/indenture. Any species, including even the main original species of a civilization, can have their rights curtailed and relegated to a lower caste, or down to full slavery.

Relegation to a lower caste can result in a small minority of servants, or an apartheid where privileged sub-species reign. Only Authoritarian empires can have such limited and targeted inequality.

Furthermore, not all population units of a lower caste species are indentured; only those units that would gain a productivity boost from being indentured while working on certain tiles and buildings are indentured. For example, a species may be made to a lower caste, and pushed into chattel labour, which grants them a boost in mineral and energy production. Consequently, any population unit of that species that is on a tile that is producing minerals or energy will become indentured. Obviously, this is a much more versatile system than full slavery.

Xenophobic and/or Authoritarian empires can have full slavery for all population units of entire species, though the original species cannot be relegated to full slaves (likely due to gameplay balance reasons). This would seem to make things simpler (as in that species will definitely be overall unhappy), but reassigning already considerable numbers of population units to different tiles can be daunting.

In the base game, there is only one option of indenturing and slavery: Chattel Slavery, which reduces a population unit to just little more than workers who produce Energy and Minerals. Changing slavery types is relatively easy, especially with the Caste setting, and is quite wise if the player intends to micromanage slaves for maximum efficiency. (However, such rights changes can only be done once every ten years, like all rights changes.)

Slaves are definitely unhappy, but their unhappiness does not affect their productivity. Obviously, voting rights are withheld from slaves too (if the people of the civilization has any voting rights, such as in Oligarchies). Of course, unhappy people are very likely to revolt, and they often desert the state for egalitarian civilizations.

SLAVE OWNERSHIP:

The risk of revolt is always manageable, as long as the government suppresses uprising. However, there is one other gameplay balancing measure against the slavery system.

Any indentured/enslaved population unit is to be “shackled” to a population unit of non-slave species (i.e. not officially relegated to a lower status). This will automatically happen, whether the player likes it or not. (There can be more slave population units than “owner” units on a planet.) If the “owner” units lose their servants/slaves for whatever reason, they suffer a considerable happiness setback.

NO OFFICIAL SLAVE TRADING:

Curiously, slave trading is not implemented in the game. Even with the content in the expansion packs, especially the Enclave system, this has not been implemented.

Explanations that have been given by both developers and long-time veterans of the game is that the current system of having one population unit per tile, and the need to have the population unit work the tile, does not make trading slave population units feasible or balanced in the long run.

Perhaps any solution to this would require a new user interface, one that would combine both the characteristics of the leader screen and the planet surface screen. This UI would only be available to slavery-practicing civilizations, and it would have dedicated tiles that are only ever used to grow slave populations. The convenience of this would have to be balanced with opportunity costs, of course.

HAPPINESS:

Every sapient population unit has a happiness rating. Of course, this would be nothing new to veterans of 4X games. As to expected, happiness ratings determine the productivity of the people, and how likely they are to cause unrest. It is par for the course for the 4X genre, and it works the same way in Stellaris. However, Stellaris does have an additional layer of complexity, specifically the factors that contribute to happiness, or lack thereof.

Firstly, there are the usual bread-and-butter factors. Population units are not subjected to taxation, but Stellaris does use a facsimile of this genre staple: living standards. Planet habitability is also another factor, as any veteran of Masters of Orion would know. The planet itself may also have special modifiers of its own.

Secondly, there are the facilities that the player can build on the planet. Expectedly, some of these affect happiness. However, Stellaris differs a bit from its peers by not having happiness-increasing buildings available early on in the playthrough. In fact, they are very rare and coveted things.

Thirdly, there are special (and often random) events that have the player making decisions. One of these decisions might affect the people’s happiness, usually in return for a price or a benefit.

Finally, and this is how Stellaris is different from its peers in this matter, there is the faction that each population unit follows. There will be more on factions later.

RESETTLING POPULATION UNITS:

If the player so wishes, the player can have a population unit resettled to some other planet. This can be useful in getting a planet to reach thresholds on numbers of population units, which are pre-requisites for upgrading the administration centre of the planet. It is also useful to fill in a tile that has already been built up by the player; this is likely to be the main reason that the player would resettle population units. After all, it is often faster to build facilities than to grow (or build) population units.

However, this convenience is not available to egalitarian civilizations. Of course, this compensates against the considerable bonuses that egalitarian civilizations have, among other drawbacks that result in lack of control over the people. That said, servile machines can still be shuffled around.

PURGING/DISASSEMBLING POPULATION UNITS:

One way to remove an organic population unit is to purge it, obviously in a lethal manner. To do so, the species of that population unit must have their rights diminished to anything below “residence”; this allows the player to select specific population units to remove. Any species that is considered “undesirables” have all of their population units immediately purged.

Obviously, this makes the population unit very angry and also disables their productivity. Until they are purged (which is a long process), they continue to occupy the tiles that they are on.

Servile non-sapient machines can be disassembled, but they would not do anything else but wait for their recycling. Sapient synthetics are definitely not fond of dissolution, and will respond just like organic species when faced with extermination.

Overall, the option to eliminate population units in such a manner has considerable opportunity costs and risks, even though purging can be done in parallel with other activities. The worst of these risks is that other civilizations whose primary species are those that a civilization has purged will be very much angry.

DISPLACEMENT & REFUGEES:

A lesser-known mechanism for the removal of population units from a colony is “displacement”.

The first case of displacement is when an existing colony from another civilization is acquired, through whatever means. If the acquiring civilization’s policy on land appropriation does not respect whoever has been there in the first place, at least five tiles will be emptied outright on random, their population units forced offworld and elsewhere as refugees if they have not been granted full citizenship. Such a case is, of course, there for the player’s convenience, specifically for bringing in other population units.

The second case of displacement is the consequences of war. A population unit that is unfortunate enough to be tagged as collateral damage might either die, or they might be lucky enough to escape. They will always escape to other civilizations, which can cause problems, or provide opportunities.

The third case of displacement is escape from slavery. In such cases, the refugees will almost always escape to civilizations with an egalitarian bent, or failing that, civilizations with policies that do not turn away refugees. Their second choices tend to be wildly random, however.

The fourth case of displacement is official species cleansing. Instead of outright violent purging, the population units of that species are eventually forced to move off-world, ostensibly due to systematic discrimination. This is less likely to make other civilizations angry, but someone will definitely not be happy.

The fifth case is, of course, outright purging. Escaping victims would not be much of an issue to the civilization that is purging them, because they are not wanted in the first place.

Fleeing refugees might be accepted by other civilizations, whether through principle or for convenience. The most obvious benefit is that the receiving civilizations gain free population units to use, but refugees also pose problems, such as introducing their factional allegiances if the receiving civilization does not have similar factions already.

PLANETS & TILES:

As any sci-fi 4X veteran would expect, any civilization would be out and about looking for other worlds to call home too. However, not all planets are habitable; most would just be useless balls of rock and dust not even worth mining. Even the habitable ones come with caveats, which will be described later.

Habitable planets have limited potential too, much of which is decided by the number of developable ‘tiles’ that they have. The system of tiles will be familiar to followers of the 4X genre; they work a lot like the tile system in Sid Meier’s Civilization series. The player places a population unit on a tile, and any resources that can be produced by that tile are produced and collected.

PLANET HABITABILITY:

There are many types of planets, most of which are of barren, i.e. lacking the means to support life. Not all of the habitable ones are usable by everyone, due to climes in which they evolve into sapient beings.

However, unlike the system of climes introduced by Masters of Orion and practised by Galactic Civilizations, there is no particular connection between the productiveness of a planet and its clime, e.g. a desert world can be just as productive as a continental world. Rather, the matching between the clime of a world and the species of the population units that would be living on it decides its productiveness.

The list of habitability ratings that planets of specific climes would offer them shows the climate preferences of any particular species. This is important to keep in mind, because the habitability of a planet greatly determines both their happiness and productivity. That said, the player should not go around colonizing any planet that he/she finds, unless his/her civilization has multiple species. Indeed, having multiple species gives the player more opportunities to own world – unless of course, the civilization happens to have Xenophobia as a Governing Ethic.

It should be pointed out here that, with the exception of Gaia worlds (more on this shortly), only a species’ own homeworld can provide 100% habitability to its people. Even worlds of the same climes cannot provide this; this is explained away as slight biological incompatibilities that a species may have with the different ecologies and micro-ecologies that the other worlds have.

GAIA WORLDS:

The jewels of the galaxy are not the most exotic substances, rarest metals or most bounteous stars, but worlds that can somehow support any kind of life. These are Gaia worlds.

Gaia worlds guarantee 100% habitability to any species, and they often have many tiles. Obviously, this makes them irresistible to just about any civilization.

COLONIZING PLANETS:

The claiming of a planet does not happen to be instantaneous; in fact, it is an arduous process that can put a drain on a civilization’s resources.

Firstly, the civilization must build a colony ship. Colony ships take the longest to build among civilian ships. Then the civilization has to pick a species as the first settlers.

After the colony ship is built, it puts a considerable drain on the civilization’s Energy economy; it is in its interest to send the ship to its destination as soon as possible. This design was implemented to discourage a civilization from having a colony ship on stand-by, waiting to snatch a planet before others do. (CPU-controlled civilizations will still do this, however.)

After the colony ship has reached the planet, the player has to choose where to place the administration centre (which is always the first building built). This is an important decision, because the administration centre will grant productivity bonuses to most buildings on the tiles that are cardinally adjacent to it. However, it is not always easy to make optimal decisions because of the presence of tile blockers (more on this shortly).

While the colony is being started – which is a process that can take many months – the colony drains energy as much as the colony ship did. There are some technologies that greatly accelerate this process, which is a short-term benefit with payoffs down the line (namely having the colony up and running earlier). The technologies may also be useful later, after the player has obtained technologies to terraform planets.

Having colonized planets, the player might want to cross his/her fingers. Some planets have nasty seeds that trigger bad events shortly after they have been settled. Some of these can even outright kill off the first population unit, especially if the player does not have the resources to prevent bad outcomes.

PLANET MODIFIERS:

A colonisable planet might have modifiers that impart their effects to everything on it. Such modifiers are rare, and they are not all beneficial.

More often than not, there are special research projects that are associated with the modifiers. These modifiers may be the reward for pursuing the projects, or they are removed by the projects, if they happen to be bad.

Most of the bad modifiers are removed by terraforming, especially if they concern weather or indigenous life-forms. Therefore, it might be tempting to consider terraforming a planet first before colonizing it, even if it is of the correct clime. Unfortunately, the game does not inform the player about which modifiers can be removed with terraforming.

BLOCKER TILES:

Taking a leaf from Galactic Civilizations, Stellaris does not have all tiles on planets available from the get-go. More often than not, some of them are blocked. The causes of the blockages are illustrated in their artwork, but gameplay-wise, the player does not need to worry more than just getting the right technology to remove them. However, the tile blockers that require later-game technologies often demand more Energy to be cleaned up. They also take longer to remove.

The main headache about tile blockers is their random placement. This can complicate the placement of administration centres when the planet is colonized. Even after the planet is colonized, clearing tile blockers take up time that could have been spent on developing tiles instead.

If the player is terribly unlucky, the player might get one of those events that happen shortly after a planet has been colonized, specifically the one that introduces tile blockers into empty tiles.

Terraforming removes all blocker tiles, regardless of their type. This can be convenient, if a planet has a ghastly number of difficult tile blockers.

TILE RESOURCES:

Most planets have tiles that have resources already on them. When the galaxy is procedurally generated, the resources are assigned to tiles on each planet with very few overarching rules other than to have some tiles of each common resource type. Therefore, there can be a lot of variation between planets. Unlike other contemporary space 4X sci-fi games, the player might want to consider not having planets specialize in one thing or another. Rather, the player should consider placing buildings that eke the most out of a tile.

If there are multiple resources on a tile and a building is built on it, only the resources that match those provided by the building can be utilized; the others are supressed. For example, if there is a tile that provides both Energy and Minerals, the player can only build either an Energy-generating building or a Mineral-generating one to benefit from the Energy or Minerals, respectively. (There are very few buildings that can generate both Energy and Minerals, by the way.)

After colonizing a planet, there might be an event that change the resources on tiles. Some are beneficial, but others can be unpleasant, if the player is unlucky enough to get the nasty ones.

SPECIAL RESOURCES:

Some tiles might have special resources, such as Betharian Stones or Alien Animals. In order to utilize these, the player needs to have the correct technology and the correct building that the technology unlocks. For example, Alien Animals can only be profited from with Alien Zoos. The player’s reward is usually a very high yield of resources.

Of course, the player could just build over the tile and keep in mind where it is for later, if the techs required are not available. However, these special resources are not shown on the icons for star systems. Fortunately, they are included as details in the list of planets that the player has colonized, so checking the list might help remind the player that they are still there.

TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE:

There should be a word of warning about any tile with uncommon bonuses. More often than not, there is a nasty caveat to them.

For example, there is a random event that grants a tile a special building. This special building is an ancient but functional alien relic that produces both Energy and Minerals. However, it would turn out that this relic is a deadly practical joke that happens to have hidden pitfall traps, which would cause the population unit that is working it to simply disappear.

Eventually, the special events that triggered the appearance of these bonuses would progress to a point where the player can make a “keep it or ditch it” decision. Ditching it may grant some temporary benefits as compensation for the trouble that they have caused, but keeping them often inflicts long-duration setbacks. Of course, if the player’s civilization could endure the setback and outlast it, the tile becomes a significant asset of a planet.

There are plenty of other “too good to be true” content in the game (and even more in the expansions) that do not concern tiles. Incidentally, most of them occur through event chains, which will be described much later.

ADJACENCY BONUSES:

The administration centre of a colony, which is always the first building in any colony, grants adjacency bonuses. Thus far in the history of Stellaris, it is the only building that has this trait. It has been mentioned earlier that it is not always possible to profit from the adjacency bonuses in the long run, due to the presence of tile blockers on a planet. Rebuilding the centre later is unwise too, because of its long construction time and the opportunity costs of having to spend time to rebuild it.

There are some special tile blockers that grant adjacency bonuses, but often with a setback (other than the blockers obviously blocking tiles from being developed). These tiles are often associated with special events that have been assigned to planets during the generation of the galaxy.

BUILDINGS - OVERVIEW:

The tiles on a planet are unproductive until a building has been placed on them for population units to work with. That said, without a population unit to work them, a building and its tile are useless too.

Buildings often incur monthly costs in Energy, unless they are already Energy-producing buildings. Buildings without population units to work them are automatically deactivated, which is convenient. The player could deactivate buildings that are being worked on to free up Energy incomes, but that is a sign that the player has been terribly unlucky or has planned poorly.

Generally, all buildings have to be built with minerals. There are a few that have to be built with Energy too and some do not consume Minerals, but are already paid for through other means.

Minerals are used for other things too (more on these later), so the player will need to plan the construction of buildings carefully. As a rule of thumb, the player should only build buildings when a fledgling population unit is about to mature.

REPLACING & UPGRADING BUILDINGS:

Buildings do eventually become obsolete, either because there is new technology that provides a better version, or the player believes that the tile could be used for something else.

In the former case, buildings can be upgraded to their next level upon obtaining the next piece of technology that are associated with them. It should be mentioned here though that the player must always build upgradable buildings at their default lowest level first, and then upgrade them to the next level. This can be tedious, but meticulous players might appreciate as this allows them to fine-tune their spending plans. Besides, upgrades happen quite quickly.

Replacing buildings is perhaps one of the most pleasant game designs in Stellaris. The player can choose to build the replacement building while continuing to have the original one being worked on. There is no noticeable setback to this.

REPAIRING & DEMOLISHING BUILDINGS:

Bad events or the rigours of war can inflict severe damage on buildings. This usually damages them to the point of loss function, but particularly nasty cases can result in the buildings being completely obliterated (often with the population unit that tended them).

Anyway, buildings that have lost their functions but have not been obliterated can still be repaired. This costs some resources, but restoring them is a process that is much faster than replacing them.

Considering the convenience of replacing buildings, there are very few reasons to demolish a building. However, what reasons there are, they are very good reasons. For one, the building might be something that the player does not want to stay around at all. This is especially the case for buildings that have been built by Spiritualist civilizations; their temples make spiritualist ethics more attractive, which is not desirable if the player’s civilization is not a spiritualist one.

UNIQUE BUILDINGS:

Some buildings are marked as “unique”. Long-time followers of the 4X genre may recognize these as facsimiles of Wonders in other 4X titles (though there are specifically-named “Wonders” in one of the expansions). Generally, the player could not readily build them like the more common buildings.

There are two types of “uniqueness”: “planet-unique” and “empire-unique”. Planet-unique buildings include the administration centre, and anything that provides planet-wide buffs, such as the Energy Grid and Mineral Processing Plant. Unlike the empire-unique buildings, planet-unique buildings have upgraded versions that make these buildings worthwhile to have in the long run. Planet-unique buildings tend to provide science points too (more on these later).

Only one of each type of empire-unique buildings can be built in any civilization. They are incredibly rare to get, and are often the product of special events or the attainment of rare technologies. It is generally in the player’s interest to build these, but where the player places them is important, because the enemy can seize them for themselves.

Furthermore, some of the empire-unique buildings can only be built on the capital world. Considering that the capital world is often the homeworld, which in turn is the first world to be fully developed, having to have existing buildings make way for them can be tricky.

There are no galactic-unique buildings in Stellaris, or to be more precise, there is no race down tech trees to get them. The expansions do introduce similar gameplay elements, but there is still no race down tech trees to get them. (Besides, the tech progression in Stellaris is quite different from other 4X games, as will be described later.) Indeed, one could argue that Stellaris has a far more reverential treatment of unique buildings.

TERRAFORMING PLANETS:

Eventually, the player obtains the technology to literally overhaul planets. This is a considerable undertaking, costing much Energy and taking a long time to work. There are two means of terraforming planets: terraforming them while they are uninhabited, or terraforming them while they are inhabited.

The first option means that a planet takes longer to be eventually colonized. The second option freezes a lot of options to develop the planet, and the inhabitants are greatly inconvenienced by the terraforming. The second option also needs an additional technology.

ABANDONING PLANETS:

It is possible to abandon a colony, even though there is no official and convenient way to do so. There is only one condition to be met: having no population units whatsoever on the planet. As for the reason to do so, the player might have obtained a far better planet, but the player wants to keep the number of owned planets low. Maybe the player has obtained a planet from another civilization that has made poor decisions with the planet.

This is easier said than done, because population units are not so easy to kill outside of really bad luck, and purging is a risky option with considerable opportunity costs, as had been mentioned earlier. The most reliable way of doing so is by opening a new colony, and then resettling population units from the one to be abandoned whole-sale onto the new one – assuming that the new one has enough tiles to house all of them.

Alternatively, the player could release the planet as a vassal, which has its own benefits and advantages, which will be described later.

(As a side note, a system with an inhabited planet cannot be relinquished by demolishing its starbase.)

RE-COLONIZING PLANETS:

The player might want to return to a planet after it has been abandoned, for whatever reason. If so, it has to be re-colonized through the usual way. Any buildings are still there, including even the old administration centre. Amusingly, this results in two administration centres on the same planet. This design oversight can indeed be exploited to create a very productive planet (including having the centres bolster each other), as well as a very defensible one (because centres produce garrisons too). However, this can take a long while.

Another reason to re-colonize planets is not to get the planet, but to gain the population unit that is spawned on the administration centre and resettle it elsewhere. Granted, this can be very costly: the wait is long, the Energy overhead has to be paid, there are the Minerals spent on the Colony Ships and the planet being colonized does count towards the number of owned planets. However, colonization happens independently of the maturity of population units on the planets that the player wants to keep.

SPACEPORTS:

Interestingly, Stellaris separates the facilities for building ships into two types: spaceports and shipyards. Spaceports are only used for building non-combat vessels, such as Colony Ships, Construction Ships and Science Ships. All colonized planets automatically have spaceports, which always function regardless of the state of their tiles and populations. Their building rates are independent of the state of the planets too.

ENERGY:

“Energy” has been mentioned more than a few times in this article already. This is one of the three tradable (and hoardable) resources in Stellaris. It is perhaps the most important one because it is also used like a currency to pay fees and the like.

Energy is spent on the upkeep of things, be they buildings, ships or space stations (more on these later). Any leftover energy (and there should be much of it) goes into a hoard. The size of the hoard starts at a respectable 5000 at the beginning of a playthrough, but gaining technologies increase the limit, allowing the player to hoard more. This is just as well, because there are many options later in a playthrough that require four-digit expenditures.

MINERALS:

Minerals are mainly used to build buildings and ships. They are also needed to produce robotic population units. In short, the minerals go into the development of the infrastructure and hard-power of a civilization.

There is a lesser need to hoard Minerals than Energy, because there are not a lot of ventures that require four-digit amounts, at least until much later in a playthrough. Rather, Minerals are likely to be consumed at a more noticeable rate than Energy, so maintaining a high income of them is more important than keeping significant reserves.

UPKEEP COSTS:

Just about everything in a civilization requires resources for maintenance. Energy is usually the payment for this, but in the case of ships and starbases, Minerals are needed too, at a default of 1% of their costs per month. Upkeeps can eventually become hefty enough to be a problem, so the player might want to consider on investments to keep the costs low, especially during peace-time when the navies are not able to earn their keep.

TECH FIELDS:

Each sci-fi 4X title is guaranteed to have some form of progression system, often given names such as “research” and “technology”. Stellaris does the same, but with some conveniences that prevent any waste of effort; this will be described later, after a quirk with its system has been mentioned.

There are three fields of science and technology: “Physics”, “Society” and “Engineering”. The Physics field concerns the usual sci-fi things that are typically flashy and bright, like lasers, plasma and fusion reactors. Chief among these are the technologies that improve Energy generation and increase the power pool for ships (more on these later).

The Engineering field also concerns the usual sci-fi things, albeit things that are chunky, hard, loud and sometimes impractical in terms of engineering, such as railguns, thick armor plates and heavy industry with unexplained processes. The most significant Engineering techs are those that involve Mineral extraction and structural scales.

The “Society” field is perhaps the oddest of the three, because it includes economic, political and biological techs. The most important techs are those that affect the populations in a civilization.

All three fields of tech are worked on simultaneously; this is something that Stellaris does differently from most sci-fi 4X titles, which usually only allow one research project at a time. This means that the opportunity costs of focusing on specific groups of technologies are not as significant in Stellaris.

These fields are further differentiated into sub-fields/specializations, typically according to the overarching function of the techs. For example, there is Propulsion, an Engineering sub-field that concerns how ships move about. Some scientists specialize in these sub-fields, so it is wise to consider changing the current lead researcher if the next research project is the specialty of others.

NO TECH TREE:

What has been described about these three fields are learned through first-hand experience and third-party sources (namely the wiki) – none of these are learned through in-game documentation. Notably, Stellaris lacks any UI screen that shows the progression of technologies. There are some techs with labels that mention that they lead to other technologies, but these other techs are not told to the player.

Perhaps the starkest difference that the progression system of Stellaris has compared to those of other 4X titles is that there are few fixed prerequisites and almost no tech branching.

PROCEDURAL SEEDING OF RESEARCH OPTIONS:

When a research project has been completed and the player is going to select the next one, the game picks several research options, but not all of those that are available to the player.

To determine the mix of options, the research system uses an algorithm on the technologies that the player’s civilization already has. The variables of the algorithm are not clear to the player, but one of them is very likely the average of the points of all techs that the civilization has, as well as the points costs of the research projects that have yet to be undertaken.

The technologies that have yet to be researched are compared to this average. If their point costs are low compared to the average, they have a very high chance of appearing as a research option, excepting rarity modifiers (more on these later). Those with higher point costs are less likely to appear, while those with costs far higher than the average would not appear at all.

This means that the player will still be able to research the most basic of technologies, barring some very bad luck. However, options with higher point costs – and greater benefits – can appear too and tempt the player into making a decision with significant opportunity costs and risk.

There are some research options that will not appear until earlier related ones have been obtained. The most obvious of these are the weapon and resource technologies. The prerequisites are mainly implemented for the purpose of gameplay balance.

Purportedly, the number of techs in specific sub-fields is a variable too. Projects in sub-fields that have not been invested much in have a greater tendency to come up as options.

RARE TECHS:

Some research options are categorized as “rare”. These have a negative modifier that makes them less likely to appear, even late into a playthrough. They are not strictly needed, but they can give significant advantages if the player pursues them, though some of them do have risks.

For example, there is “Wormhole Stabilization”. This allows a wormhole to be stabilized, effectively turning it and its counterpart elsewhere in the galaxy into stable, freely usable Gateways. Obviously, this is a great advantage if the player has the strength to force through whatever is on the other side, but the wormholes work both ways.

Undertaking the research of rare techs is not without problems. Rare techs apply a penalty to the research speed if the lead researcher is not an expert in the sub-field that concerns the rare techs. Having a stable of Scientists with different expertise can be impractical, however. (The Leviathans expansion addresses this problem with an expensive alternative.)

DIFFICULT TO FOLLOW PLANS OF TECH PROGRESSION:

The lack of tech tree screens and the procedural seeding of research options make the planning and following of tech plans much more onerous than some 4X sci-fi veterans would like. Of course, the player could look at the wiki of the game and keep the point costs of the options in mind, albeit at the cost of immersion. Even so, these players would have the dilemma of following their master-plan or going after rare options when they appear.

Of course, there is the argument that this is a deliberate design decision on the developers’ part; they are well aware of the usual tropes in sci-fi 4X gameplay, and they are not fond of the typical tech trees, as are a number of jaded players (myself included). More importantly, this system does work in preventing players from coming up with guaranteed gameplay-imbalancing plans of progression, or at least plans that do not have considerable opportunity costs.

SCIENCE POINTS:

Most sci-fi 4X titles use point-based systems for research options; they are often nicknamed “science points”. The points are generated through pouring other resources into making them, like in the Galactic Civilizations titles, or making the buildings that generate them. Stellaris does the latter, but diverges in how science points are applied.

Where the other 4X titles apply them automatically to any research project that is being undertaken, Stellaris lets the player hoard them, if he/she so chooses. This is done by simply not taking any offered options.

There are few reasons to do this, and the game does alert the player about not having undertaken science projects with a rather annoying audio clip. However, the player could do this in anticipation of getting bonus research options, which will be described later. For example, the player may be expecting that he/she would get a bonus option from the wreckage of enemy vessels that have equipment that the player’s civilization can reverse-engineer. He/She can hoard points so as to accelerate the research of said equipment.

The keyword here is “accelerate”. Not all of the hoarded points can be spent immediately. Rather, they are spent at the same rate as the civilization’s rate of science point generation. In other words, the researching goes twice as fast.

The main opportunity cost here is that the lead researcher in the field of science that has been put on the backburner continues to age, so the player might not want to do this if the scientist is already close to passing away. (There will be more on the aging of leader characters later.)

Any currently undertaken research project can be switched out for another at any time. The progress that has been made is not lost, and the project remains an option after another project has been finished. It will not count as a bonus option though, and will continue to take up a slot for a regular option.

Such nuances are not told to the player, but then, only experienced players would be able to take advantage of them.

BONUS RESEARCH OPTIONS:

The player might be lucky enough to gain opportunities to obtain special or regular techs through advantageous circumstances. However, more often than not, the player will need to undertake research of these techs. Conveniently though, the options for these techs will always be there in the lists of projects that can be undertaken. The player could choose to postpone their undertaking, at least until more favourable circumstances come up, such as the emergence of a scientist with the appropriate expertise.

SCIENCE COST INFLATIONS:

The science point costs of official research projects increase as a civilization’s number of owned systems and planets increases. The number of planets, in particular, is a greater inflation factor.

This setback was implemented for the purpose of gameplay balance, in an attempt to prevent massive civilizations from getting too far ahead by simply having many assets. This is a notable difference that Stellaris has compared to earlier sci-fi 4X titles, which usually have the biggest empires winning playthroughs.

Therefore, the player has to be meticulous in planning the expansion of his/her civilization, with an eye out for optimizing productivity of planets.

RESEARCH PROGRESS BONUSES:

Fortunately, there is a long-term way to counter the inflation: progress bonuses. These are percentage-based multipliers to the worth of each science point, and each field of science has its own bonus statistic.

The main contribution to these bonuses is the skill of the scientists that have been chosen as lead researchers. However, there are other sources of bonuses, such as a certain Edict, other even more specialized Edicts, and certain empire-unique buildings, to name a few.

That said, there are some modifiers that are not bonuses but are penalties instead. These are often applied by rare techs. In the base game, this penalty can be addressed by having the correct expert lead the research project, but as mentioned earlier, maintaining a stable of experts can be too much.

REPEATABLE SCIENCE PROJECTS:

Repeatable science projects only appears at the very end of a playthrough, when the dominant civilization in the galaxy has already researched all techs there ever were. When this has happened, repeatable techs begin to appear as options for this civilization, and eventually there are only ever these. As the name of their category suggests, these techs can be researched over and over, granting cumulative bonuses each time. These have the highest science point costs in the game, but they allow the civilization to simply break through any gameplay balance limitations that had been put in place, if only to surge faster towards the end of the playthrough.

SPECIAL RESEARCH PROJECTS:

There are some special research projects that are not listed together with the official ones. Rather, they are included in the Situation Log (which is practically Stellaris’s equivalent of a quest log in RPGs). Special research projects have their progression measured in days instead of months.

Special projects can be grouped into two types, according to how they are enacted. One type only requires that the player has a Science Ship on-site to undertake the project; this one will not affect the official research projects. However, it does freeze the Science Ship’s activities, at least until the player cancels the project (upon which all progress made is lost and has to be regained from scratch).

The other type does not require a Science Ship. Instead, they need investments of science points. They do not hold any Science points like regular projects do, however; if they are disrupted in any way, all progress is lost, though the points are refunded.

More importantly, this type of special research projects will take priority over any current normally chosen research project. Its progress tracker is shown in the Situation Log instead of the research UI.

A select few research projects require Construction Ships or even Transport Ships to undertake them. In these cases, the type of ship required would indicate the rewards that the player would get: using Construction Ships usually means special ships can be obtained relatively free, whereas Transport Ships might result in special population units or leaders being recovered by the armies on the Transports.

The problem with these particular research projects though is that they often have timer limits; failing to undertake them in time means that the opportunity is lost. Considering that Science Ships would be going to places where Transports or Construction Ships might not be able to go, clinching these projects can be difficult. On the other hand, the player could still have the foresight of having a Construction Ship and/or Transport follow each Science Ships around.

MODIFYING POPULATION UNITS:

Genetically modifying any organic species or redesigning machine models are special research projects that are parked under the situation log too. Their science costs are proportional to the number of population units of a species that the player wants to modify and the number of traits that the player wants to give to them. The projects also have a fixed base cost that is added to the variable costs.

The main reason that the player might want to modify population units is to produce sub-species, either as an improved version of the original or a substitute when the original does not fit the player’s schemes. However, these special projects are very expensive and time-consuming undertakings (mainly due to the aforementioned fixed costs). Therefore, the player might not want to do them unless the benefits far outweigh the opportunity costs.

For example, a civilization’s main species may have dozens of population units, thus making the special projects to reengineer them particularly long and daunting. However, if the benefits are considerable, such as a significant boost in inherent happiness, it might be worthwhile to enact them so as to reap the fruits down the line.

Of course, the player could invest in infrastructure that provides a lot of Society science points. Yet, the opportunity costs for this strategy are that all those Minerals that went into the Society-generating buildings, and the tiles that they are built on, could have been used for something else.

THE GALAXY:

Much as some (including myself) would like to think that space is three-dimensional and should not be anything simpler, the galaxy has been described by researchers as a two-dimensional plane in its entirety. Most sci-fi space 4X titles cleave to this description, for both believability and gameplay simplicity. Stellaris would do the same.

Any galaxy that is generated by the game is composed of star systems that are connected to each other on a 2D plane, or rather, a 2D annulus (ring) to be precise. The centre of the galaxy is composed of dense clusters of stars, and is curiously inaccessible. Therefore, almost all playthroughs would be about civilizations trying to expand and reach around the galaxy.

SOME VERTICALITY:

That is not to say that the galaxy is completely flat, like galaxies in so many other space 4X titles. The galaxy in Stellaris is not a piece of 2D artwork; rather, it is a lattice of icons in 3D.

Indeed, some of the star systems are located higher or lower than the others on the galactic plane. In fact, one of them could be right on top or below the other.

Unfortunately, this causes problems just as much as it improved the complexity of the game. The problem is an issue of parallax; it can be difficult to notice that the icons for two star systems are overlapping each other.

STAR SYSTEMS:

Each star system is also represented as a 2D plane; even the orbits of planets around their sun are located on the same plane.

Speaking of orbits, the planets, stars, moons and other celestial bodies are always situated on the same spots in their star systems all the time throughout a playthrough; planets do not even orbit around their stars. This is a lost opportunity for more complexity in gameplay, but perhaps this was so for the sake of simplicity.

Planets and non-star bodies that are not moons almost always appear around stars. Habitable ones are almost always in systems with orange, yellow or sometimes red stars. On the other hand, the types of stars do not appear to determine what kind of climes that a planet would have, at least not with any predictable certainty. The types of stars do determine what resource that they provide, however.

There are observations about some star types that are close to being guarantees. Habitable planets almost always never appear in systems with pulsar stars and black holes, or any stars that inflict penalties on ship movement. Speaking of which, these star systems are often at lynchpin or chokepoint locations, making them useful defensive strategies, e.g. having defense platforms loaded with armor or hull-shredding weapons only to complement a starbase that is in a system with a pulsar.

In the Niven build of the game (which this review is based on), there can be more than one star in a system, representing binary stars and trinary stars that are described to exist. Having more stars in a system might be a good thing, because more stars means more Energy sources, and perhaps more planets. However, the planets often have at best a decent number of tiles, apparently because of gameplay balance measures.

STARBASES:

Claiming an unowned system is as simple as planting a starbase in it. Building starbases requires some Minerals, and a considerable amount of Influence, which will be described later.

All default-level starbases only cost a small amount of resources every month to be maintained, and all of them are armed. However, starbases do take a while to build, their default level is laughably weak and without upgrades, it does nothing else other than float in space.

A civilization can choose to upgrade its starbases. Upgraded starbases are more capable in defensive combat and are harder to bring down. They also attain slots for the installation of modules, of which there are two types, which will be described later. Upgrading starbases is costly, however, and they take a long time, so the player has to be careful about which ones to upgrade. (Generally, every system with a colonized planet or more should have an upgraded starbase, because of limitations on the mechanism of invasions that will be described later.)

However, the player cannot have many upgraded starbases. Firstly, upgraded starbases cost more to maintain. Secondly, there is a “soft cap” on the number of starbases that can be upgraded. It can be exceeded, but doing so significantly increases the maintenance expenses of the starbases, including any expenses for their modules. The soft cap can be raised by having more population units, or through certain techs, but the soft cap will always be a limitation.

Letting systems go is as easily done as dismantling its starbase. However, the player has to downgrade the starbase if it has already been upgraded; there is no option to immediately outright dismantle the starbase, regardless of its upgrade level. This tedium is caused by limitations in the user interface for starbases.