INTRO:

The Battletech IP is about a dystopian sci-fi future where humanity has ventured into space but not exactly achieved the prosperity that the cosmos promised. The IP actually has a lot of rich lore, and despite being sci-fi, there is a lot of focus on the improbability of otherwise absurd would-be technologies.

For better or worse, not many people could see past the most obvious things about Battletech: its giant walking war machines. This rather narrow perception of the IP was so pervasive such that when the video game scene introduced the IP, the Mechwarrior line of games was better remembered than the name of the IP itself.

Consequently, the gameplay of most Battletech-licensed games focused more on driving a BattleMech around (and they invariably carry the “MechWarrior” name somewhere in their title). Not even FASA Interactive’s MechCommander series corrected this.

Now, Harebrained Schemes – in collaboration with Piranha Games (current holder of the MechWarrior license) – is the latest game developer to try to make a game with the Battletech IP.

BACKSTORY SETTING…:

As mentioned earlier, BattleTech is set in the far sci-fi future, but it is far from being a utopian vision. Tremendous inequality is still the norm, and most nations have progressed/regressed towards inherited rule because democratic systems are just too slow for interstellar governance (or at least that was the excuse). The “greatest” of the rulers-by-inheritance are the so-called Great Houses, who rule over vast swathes of known space, which by the way is called the “Inner Sphere”.

There are a number of canonical eras in BattleTech lore. In the history of the IP, the starting era was the mid-3020s, back when BattleTech was called Battledroids. (It was renamed afterwards because Lucasfilms has a very aggressive litigation arm.) Most video games prior to this one used the 3040s and 3050s settings instead, when the Fourth Succession War and Clan invasion happened, respectively. Some even used the particularly violent Jihad era as the setting.

Curiously, quite a number of recent BattleTech-licensed video games have chosen not to start their stories in those turbulent times, but rather much earlier. In the case of this game, it is back to the mid-3020s. This is perhaps just as well, because one of the founders of Harebrained is none other than one of the creators of the BattleTech IP.

… AND SLIGHT DISAPPOINTMENT:

However, if the player expects to be partaking in one of the major Inner Sphere wars, the player would be mistaken. Instead, the game takes place in one of the Periphery regions, which are at the fringes of the Inner Sphere. Specifically, the region that is used as the setting is the “Rimward Periphery”. This region has realms that may not be as powerful as the Great Houses, but they retained a lot of their technology and capacity for warfare, more so than most other Periphery realms.

This particular backdrop in the BattleTech universe is actually FASA Interactive’s own version of the malleable and customizable setting that often appears in RPG books. Incidentally, such settings often involve a lot of chaos and upheaval, such that the consequences of anything that have happened would never lead to canonical statuses.

Therefore, there is the criticism that this game is not being ambitious in its story-telling, especially considering that its promotional trailers and intro splash suggested that it might be so.

Indeed, it would not be until after the launch of the game that Catalyst Game Labs – the current developer of the BattleTech IP – would acknowledge that the events in this game’s story campaign are canonical. (They would still have a hard time implementing the Aurigan Reach into the later eras, however.)

PREMISE:

The player can begin a playthrough in campaign mode, which contains most of the storytelling effort that Harebrained has invested into the game. However, as mentioned already, the player should not expect the story to be tied in much with the major canonical happenings in the Inner Sphere.

Indeed, the premise of the story campaign might even seem cookie-cutter to long-time followers of story-telling. A monarchy – in this case, the Aurigan Coalition – has a recent upheaval due to the betrayal of relatives – in this case, the betrayers are an uncle and a cousin – that are close to the ruling family. The ruling family – House Arano – has only one survivor, Lady Kamea. She happens to be the most prominent protagonist whose name is acknowledged by every significant character.

Such a story of betrayal has been told many times before in medieval fantasy stories. In fact, the canonical betrayal of Stefan Amaris the Usurper in the history of the Inner Sphere comes to mind. Sole survivors of betrayals are nothing new either.

Of course, the sole survivor seeks vengeance, and needs allies for this purpose. This is where the player character officially enters the story. In typical Battletech fashion, the player characters are mercenaries, i.e. skilled soldiers whose employment is temporary and disposable at worst. Although the storytelling begins with Kamea narrating that the player character carried the day in her return to power, such protagonists are ultimately consigned to the oft-overlooked nooks and crannies of documented history.

In other words, Harebrained Schemes’ writers would not be strangers to such a story; they already have made a few Shadowrun-licensed games. Shadowrunners in that IP are not that far off from the mercenaries in Battletech in terms of the impact that they would have on the story-telling, i.e. official in-universe historical records are hazy or vague as to what the protagonists did. Thus, there is the impression that Harebrained was not being particularly ambitious in utilizing the lore of the IP.

STILL STERLING PRESENTATION:

On the other hand, Harebrained still has invested considerable effort into presenting the story. This is evident in the use of music, which will be described further later. There are lavish hand-drawn artwork, animated to have dioramic appeal.

Last but definitely not least, there is the writing. Curiously, most of the storytelling is delivered through statements and remarks by characters or documentation that is written in-universe, rather than an omniscient narrator as in the Shadowrun titles.

STORY CAMPAIGN & CAREER MODE:

In actuality, most of the gameplay – including that in the story campaign – is built around the “Career Mode”. The player is the leader and main decision-maker of a small mercenary outfit. (There will be elaboration on the word “small” later; this would be a complaint, by the way.) In-universe, this outfit is called a “command”.

The mercenary command starts in rather dire straits in the story campaign. The player’s options are severely limited, and the player would be doomed if the player does not pursue the story. To do anything more, the player has to pursue the story-related missions in order to unlock more of the features that would otherwise be in a playthrough that is started in Career Mode.

The story campaign also tamps down on the composition of enemy forces, either limiting their numbers or total weight until the player has passed certain milestones in the story. The Career Mode does not have such easing-in. This gives the impression that the story campaign is one long extended tutorial for Career mode.

After the story campaign has concluded, the mercenary outfit is released from service to House Arano with honours. At this point, the playthrough reverts to the usual mechanisms of Career mode, albeit the player has a significant backer in the form of the royal house that has regained its rule.

PASSAGE OF TIME:

The Career (and story) mode depends on a simple system of time to refresh its content for the player to peruse.

The passage of time is measured in days, weeks and months; the days are presumed to be based on the standard Earth day. A week has seven days, and a month has four weeks. Going into the next month is a significant occasion, as will be described later.

The passage of weeks and days are actually not really that important in the gameplay. They are mainly there for the player to keep track of when wounded or otherwise inconvenienced pilots would return to duty and/or when BattleMechs become battle-ready. There may be the impression of urgency from some of the story-related missions, but the player can actually take his/her time performing them.

THE MERC OUTFIT - OVERVIEW:

In the Career and story modes, the gameplay is split into two major components. One component is for the battles, whereas the other is for the management of the mercenary outfit. This article would begin with the latter first, because the gameplay for the former in those modes greatly depends on the player’s managerial decisions.

THE ARGO:

The mercenary command has a space vessel of its own. Indeed, in BattleTech lore, the operation of one is essential for a competent mercenary outfit, which needs to wander through space looking for work.

Anyway, the vessel, called the Argo, is practically the mobile home of the mercenaries. This is also where the mercenaries keep, maintain and modify their Mechs.

In the story campaign, the player begins with only the Leopard, which is among the smallest dropships that an outfit can have. It is inadequate, but the player would eventually get a much bigger vessel – the Argo. Incidentally, the Argo is also the vessel that the player starts with when playing Career Mode from the get-go.

(The vessel is a one-of-a-kind vessel that was conceived for this game. For one, it is incapable of atmospheric entry, yet unlike other space-only vessels, it is not a Warship. The backstory of humanity’s mostly-forgotten past of exploratory space travel conveniently accommodates its conception.)

Anyway, the Argo is never under attack in any way during any point in the gameplay; the Rimward Periphery is not a region that is known for having a lot of Warships (or even “Pocket Warships”, which are smaller naval vessels). The region does have a considerable problem of piracy, but the player should not expect actual gameplay mechanisms about engagements in space.

Therefore, the player either would be relieved that there is no significant gameplay complication from having a very large unarmed vessel, or would be disappointed because there is a wasted opportunity for space combat. (That said, there are text-only events where the Argo does come under attack by pirates. Its only defense is the otherwise armed Leopard dropship that is attached to it.)

SIMPLIFIED MAINTENANCE:

In the Career (and story) mode, the operation of the Argo does incur costs. These are inclusive of the costs of paying the crew, paying for their board and food, keeping Mechs battle-ready and such other necessities. The player does not have to worry about the exact details, because the player has an Executive Officer (XO) that handles such things. Therefore, the maintenance costs of the Argo and its assets are only represented as a summed amount that is incurred monthly.

The costs only become higher over time, due to reasons that will be explained shortly.

RESTORING THE ARGO:

In the story campaign, the Argo is a salvaged ship, to phrase its initial state in the kindest way. Although its basic functionalities are available, many of its systems are decrepit from neglect. Fortunately, they are not completely busted, and can be restored.

Restoration takes a lot of money, but expertise is not an issue because the ship conveniently starts with a crew of specialist engineers. The player only needs to pick a restoration project to start and pay the costs up-front. The engineers then give the time to completion, and are generally guaranteed to finish it by then.

A considerable portion of the gameplay in the Career (and story) mode is the player juggling money in between spending it on the outfit’s BattleMechs or on the Argo. The latter would reduce a lot of the downtime in between missions, but each upgrade also comes with additional operational costs that are cumulative. In other words, a gradually restored Argo not only makes the pursuit of missions easier and quicker, it also increase the expenses of the mercenary outfit over time, thus necessitating the higher rate of mission-taking.

NO MANUFACTURING-RELATED GAMEPLAY:

The Argo is described as having advanced facilities for repairing and maintaining BattleMechs and a storage depot that can pack a lot of Mech parts, among other things. There is even a remark by one of the characters that its automated systems can manufacture Mech limbs rather readily.

Yet, there is no gameplay about manufacturing parts. Rather, the Argo’s facilities are implied to be the reason for how the technicians in the Mech bays can cobble together even the biggest and most sophisticated Mechs from salvaged parts.

TECH AND MEDICAL POINTS:

The effects of the facilities on the Argo are further simplified to the feature of “Tech points” and “Medical points”. Tech points determine how efficient the technicians are at modifying Mechs, whereas Medical points determine how quickly Mech pilots (called “MechWarriors” in-universe) can recover from injuries. They are also used in some random events; random events will be described later.

STORAGE:

Before describing the gameplay element of readying BattleMechs, the Argo’s storage capabilities and limitations would be described.

Firstly, the Argo has a vast cargo hold. Space limitation is not an issue, even if the player has amassed a lot of stuff. There is no cost to having a massive inventory too. (Presumably, being in a space vessel with controlled environments means that there are no issues like exposure to the elements to worry about, but that may not be so in reality.)

However, bringing the stuff out of storage for use is another matter, which will be described later. That said, most of what would be going in and out of storage are Mech parts and chassis (or “chases”, for the plural term of “chassis”).

READYING OF BATTLEMECHS – OVERVIEW:

The following sections are about getting BattleMechs ready for battle and tricking them out to suit whatever whims of the player and (hopefully) the needs of the upcoming mission. The gameplay designs of the BattleMechs in actual battles are described later.

ONLY EVER ONE LANCE:

The Argo may be able to store many BattleMechs. It can have up to three Mech Bays, allowing up to 18 Mechs to be battle-ready.

Yet, the player only ever fields a lance of BattleMechs, i.e. four of them. The player can have more than just four Mechs in Career playthroughs, but only four of them go into the battlefield. This also includes battles in Skirmish mode.

This is a considerable limitation, especially to players that have played earlier BattleTech-licensed strategy games, namely the MechCommander series. Of course, the MechCommander titles lack many of the gameplay mechanisms in Battletech in order to implement their real-time gameplay without too many complications. Yet, in those games, being able to have more than just one lance of Mechs on the ground makes for more convincing battles.

NARROWER SCOPE:

On the other hand, the setting of the Rimward Periphery means that there are not as many BattleMechs here as there are elsewhere. The numbers are certainly much lesser than, say, the numbers in the Succession Wars. Therefore, the military forces in this region of known space are much more diffused, and the battles are much less ferocious. (In-game, there are veterans of the battles in the core regions of the Inner Sphere that would mention this difference.)

The circumstances of this setting are used to narrow the scope of the battles in this game, as will be described later.

“HEAVIER IS BETTER”:

Unfortunately, the narrower scope of battles is merely a salve to any disappointment that would be had from this limitation. One of the characters in the story campaign would sum up the consequences of this limitation in just one phrase: “heavier is better”.

There are few reasons to go for lighter lances, especially in the current build of the game. Even in missions where speed is important, e.g. catching prey before they escape and exit the map, the player can compensate by having Mechs with skilled pilots and long-range weaponry knock out fleeing enemies.

There is a wasted opportunity to field Mechs of varying weight classes and coming up with strategies to have them complement each other.

MECH CHASSIS:

The chassis of a Mech determines the variety and amount of equipment and hardware that can be installed onto it.

Mech chases are kept in storage without anything on them. If the player sells them off, they are sold without the parts, which in turn partially explains their noticeably low price compared to the (often ridiculously high) price of whole Mechs. That said, the player would be doing this a lot anyway; a major component of the mercenary outfit’s income is the sale of chases of Mechs that have been completed from cobbling together partial salvage (more on these later).

There will be more statements on Mech chases, where pertinent.

COMPONENTS:

A significant appeal of the Battletech IP and its licensed games is the kitting out of Mechs. Components are installed onto the aforementioned chases of Mechs to give them weapons, armor and such other things that are important in battle.

Like in the table-top game and just about every BattleTech-licensed games, almost every component that can go into a Mech can go into other Mechs too. This seeming universality of Mech components is explained away in the lore of BattleTech as a beneficial long-term consequence of the conception and evolution of BattleMech designs.

Still, a component has to be installed into a Mech, and this takes time. More expensive components are more complex, and thus takes more time to be installed.

Curiously, removing components does not cost any time. This is useful to keep in mind, especially if the player intends to shift components around or have a Mech inherit components from a Mech that is going to be put into storage.

REMOVING AND INSTALLING COMPONENTS COST MONEY:

Both the removal and installation of components cost money. Although the player gets to preview the changes that could be had from the modification of a Mech, any actual changes to the Mech must be paid for. This is a very important consideration. Together with the time for installation, it is a limitation that prevents the player from making changes willy-nilly.

As for the magnitudes of the costs, they are proportional to the default costs of the components. Therefore, more expensive and advanced components cost more to be installed and removed. (The costs for removal are much lower than the costs of installation, fortunately.)

The Mech Bays are where the kitting out of Mechs happen and where they are kept ready for battle.

Initially, there is only one Mech Bay, which allows up to six Mechs to be readied. Although the player can field only four Mechs in any battle, the player would want to have more Mechs just in case any Mech gets damaged.

Damaged Mechs cannot be fielded until they are fully repaired. Repairs can only happen while they are in a Mech Bay, and damaged Mechs cannot be sent into storage until they are repaired either. Until then, they occupy space.

Furthermore, and this is perhaps the most important reason to have available space in the Mech bays, is that partial salvage of Mechs is cobbled together and put it into a cubicle into the Mech bays. Actually, a cubicle is not needed for this to happen, but if the player wants to use the new Mech in the future, having an empty cubicle for it would have been convenient instead of having to swap out an existing Mech for it.

Hence, there is a need for space to keep both damaged and battle-ready Mechs, as well as space for Mechs that are being modified and Mechs that would be obtained from completing partial salvage. The first Bay alone is not likely to be enough to satisfy all of these needs.

That said, the player can have up to three Mech Bays. Each will incur maintenance costs, so the player will want to carefully consider opening the second and – especially – third bay. (Opening Mech Bays also add Tech points to the Argo.)

SENDING MECHS INTO STORAGE:

When Mechs in the Mech Bays go into storage, all of the stuff on their chases is removed and their chases are stored separately. Somehow, this process happens near immediately; for whatever reason, the Mech techs of the mercenary outfit are particularly skilled at doing this. Furthermore, no costs are incurred, conveniently.

Of course, this is for the sake of gameplay expedience, specifically the clearing out of unwanted Mechs.

BRINGING MECHS IN FROM STORAGE:

Bringing Mechs from storage into one of the Mech Bay cubicles is another matter. The process takes at least one day, during which the technicians cobble the Mech together using its stock parts. This process is implied to be faster than the process of modifying Mechs beyond their stock load-outs because the chases were originally designed to be assembled together with their stock parts.

A mech that is brought into the Mech Bay in this manner would be equipped with the components of its stock design. These components are taken from storage. If there are not enough components, the Mech comes into being anyway, but without the components that are short on supply. This will not speed up the process, however.

TOOLTIPS ARE VERY IMPORTANT:

For better or worse, detailed information about Mechs is presented through tool-tips that appear when the player hovers the mouse cursor over things that are displayed in the Mech Bay screen. (This also precludes the game from being adapted so easily for the console platforms.)

For example, detailed information about a Mech’s capability in close combat is not readily visible in the Mech Bay screen. To get this, the player needs to hover the mouse cursor over the “Melee” rating bar of the Mech. The tooltip appears after half a second of waiting.

USELESS METERS:

That said, the meters that are supposed to be estimates of a Mech’s capability are quite useless to a meticulous player. Indeed, they may even be misleading.

The worst example is the meter for Heat Efficiency. Giving a Mech a Heat Bank mod causes the meter to fill out significantly, even though the benefit of the mod is a lot less than the bump in the meter would suggest.

Another example is the meter for overall range. This meter gets confused by the inclusion of both very short- and very long-ranged weapons in the same Mech with nothing else in between.

It is unfortunate though that in the official build of the game, there does not appear to be any display option for swapping the meters for the detailed numbers of the tooltips.

BODY SECTIONS:

Each Mech that is featured in this game has been designed with certain phenotypic homogeneity. Each of them is bipedal, has one head and has two arms or facsimiles of them. Their torsos are separated into three sections: left, right and center. These body sections have significance in both the Mech Bay gameplay and in actual battle.

(Actual battle also involves the rear sections of the Mechs, which will be described later.)

In the Mech Bay screen, the aforementioned sections are where the player puts components into; this is of course a simplified visual representation of the things that go into a Mech. Still, this has been the system that is used in the table-top game, and has been so for the MechWarrior games too.

The MechCommander games used systems that are different, but were maligned for simplifying things too much. For one, the MechCommander titles used RNG rolls to decide whether weapons get destroyed when the arms and torsos of Mechs become vulnerable to catastrophic damage.

Therefore, the use of sections in this game gives the player more certainty. This certainty is much needed, because a lot of the gameplay during battles is dependent on RNG rolls; there will be more elaboration on this later.

SLOTS:

Each section is represented with a number of slots. Typically, bigger Mechs have sections with more slots than smaller Mechs, meaning that bigger Mechs can mount more components.

Anyway, the slots represent the amount of space in that section; this space is not to be confused with tonnage, which is a different factor that will be described later. (The table-top game has further categorization of the slots, but the video games including this one tend to use simpler adaptations.)

Each component takes up a number of slots; the minimum is one. The rules on their sizes in terms of slots lack any narrative or technological consistency though; this stipulation is mainly for the purpose gameplay balance.

(The writers for the Battletech IP try their best to rationalize the reason for a component taking up a lot of space, but much of the explanation is still either absurd science fiction or incredulous vagueness.)

That said, any component that the designers deemed as being too overpowered if stacked in multiples would have massive size in terms of slots.

For example, the Heat Bank is a component that increases the Overheating threshold and Heat capacity of a Mech (more on these later); having many of these means a Mech can fire a lot of weapons in a few turns without overheating too early. Thus, the Heat Bank takes up more than four slots, ensuring that it cannot be installed in anything other than the torso sections and arms. There would not be much space left for other components too.

HARD-POINTS:

Hard-points are intrinsic designs in the chases of Mechs. Hard-points determine the hard limits on the types and numbers of weapons that the Mechs can wield. No matter how much tonnage that the player can scrimp and how many components that the player can squeeze into the slots, the limits due to hard-points must be observed.

CHASSIS VARIANTS:

The silhouettes of Mech chases are just that: shapes. Their actual roles in battle are determined by their systemic quirks instead; these quirks are the reason for variant models within the same chassis line. The variations are often differences in the number of hard-points.

For example, there is the Catapult chassis, which exhibit the most variation with the most obvious visual differences. The mainline series, the C-series, has the Catapult performing its intended and name-sake role: indirect-fire support. Consequently, the C-series has mostly missile hard-points. In contrast, the K-series of the Catapult line swaps the missile hard-points for energy-weapon hard-points. Thus, instead of boxes of missiles, the Catapults appear to have laser guns for ears.

Perhaps the most sought after chassis variants are those that have differences in their other statistics. The most prominent of these are Star League-era Mechs, which often have better heat dissipation than the (much more economical) models that come later.

TONNAGE:

All Mechs have a nominal weight rating; the exact canonical weights might actually be different. In the lore of the IP, the weight ratings are there for the purpose of matching the load-outs of Mechs to the output of the reactors that power them. (Unfortunately, reactors are not an upgradeable element of Mech builds.)

Anyway, the weight ratings are referred to as “tonnage”. Tonnage can be further broken down into two types: tonnage that is already taken up by the integral workings of the Mech chassis, and the tonnage that is available for things that are installed onto the chassis.

The former often determines the innate performance of the Mech. For example, the Banshee assault Mech has a lot of this for its motors and musculature that make it among the most mobile assault-class Mech. A Mech that has a lot of these is likely to have the role of fighting in close combat. Incidentally, there is not much else that the player can do with these Mechs because they do not have the spare tonnage to be equipped for any other roles.

The latter tonnage is much more interesting. This is simply because the more tonnage there is for components, the more options that the player has.

The ratios of the two types of tonnage are the main factor of difference between different Mech chasses. For example, the Awesome has the same weight rating as the Zeus, but the Awesome is known for having more capacity for components in return for slower mobility. (The Awesome is more sluggish than other assault Mechs of the same weight.)

Obviously, a Mech cannot be fielded if it goes over tonnage; the player cannot even complete its modifications until this has been solved.

Tonnage does not matter in actual battle. For example, losing an arm would have made a Mech lighter, but this will not increase its speed. (The explanation for this is that the imbalance caused by missing limbs or torso sections offsets any gain in speed due to loss of mass.)

WEAPON RANGES:

Each weapon has ranges in which it is the most effective; this effectiveness according to range is implemented as accuracy penalties that the weapon would suffer if it is used at any other range.

Conveniently, the ranges of weapons are visually represented as arcs in translucent grey. If the weapons have overlapping arcs, the overlapped regions become more opaque, thus indicating the best ranges at which the Mech can use all of its weapons.

COMMON WEAPONS - FOREWORD:

All Mechs can make melee attacks, but a Mech without guns is not going to do much in battle anyway; coming to grips with the enemy makes a Mech vulnerable to being gunned down, or even counter-charged. Therefore, all Mechs need guns for the (many) moments when close combat is not feasible.

There are many types of guns; this is one of the appeals of BattleTech (and also one aspect where it is absurd). Each type of gun comes with setbacks and advantages, and subtypes within the same type generally has statistical progressions that exchange advantages for setbacks and vice versa.

In other words, there are few sureties in the builds of Mechs. The player must keep the advantages and setbacks in mind so that the player’s Mechs can contribute to battle as efficiently as they can.

The following weapons are ubiquitous weapons that can be had in the open markets. More exotic weapons are described in their own sections later.

LASERS:

Lasers are the second-most absurd sci-fi category of weapons in BattleTech lore. The IP was conceived during the 1980s, when lasers were trending in the sci-fi genre of stories. Of course, as the years gone by, the realities of experimental laser weaponry have made sci-fi lasers seem ridiculous. The writers of the IP have never bothered to reconcile such differences, even though they put a lot of effort into explaining other sci-fi technologies in the IP.

Anyway, lasers in this game are as one would expect from lasers in video games. They are direct-fire weaponry and thus work best with clear line-of-sight. They have no recoil, so they have relatively better accuracy than other weapon types.

All lasers generate considerable heat; this setback will be a major consideration in heat management, which will be described later. Indeed, one of the best ways to decide which laser to install into a Mech is its damage-to-heat ratio.

The main appeal of lasers is that they do not require ammo, meaning that Mechs that have them can keep shooting as the lasers are functional and they are not overheating.

There are two common archetypes of lasers: medium and large. Medium lasers are meant to be used at mid-range, in which they are the most accurate weapons. They have the poorest damage to heat ratios among lasers, however. Large lasers have longer reach and better damage-to-heat ratios than medium lasers, but are notably bigger and heavier.

Small lasers are placed under the category of support weapons, which will be described later.

AUTOCANNONS:

These are practically large-calibre ballistic guns. They require ammunition, which does take up space and have weight. Still, this is par for the course and not really a setback.

The main appeal of autocannons is that they do not generate much heat. They also have high damage output per hit, more so than almost any other weapon type. They also stagger their enemies more severely than other weapons. (The gameplay element that involves staggering will be described later.)

The worst setback of autocannons though, is their size and weight. Most of them take up at least two slots each, and the lightest of them still weighs five tons.

Furthermore, there is the matter of recoil, which is systemic to all ballistic weapons. This will be explained further later, but suffice to say that this prevents them from being fired in subsequent turns.

SHORT-RANGE MISSILES (SRMS):

Short-range missiles (SRMs) are dumb-fire missiles with no guidance, and are intended to be used to hit enemies up-close, as their name suggests.

They are perhaps the most peculiar weapons; heavy autocannons operate at their ranges and can inflict more total damage, whereas medium lasers are more accurate. Thus, their main appeal is the number of missiles that they unleash per volley; at least one of them is more than likely to hit the target, even with terrible RNG rolls.

Their other appeal is that SRM launchers are among the lightest weapons around, other than medium lasers.

LONG-RANGE MISSILES (LRMS):

Missiles have been effective long-range weapons, and so they remain in the sci-fi future of BattleTech in the form of the aptly- and simply-named long-range missiles (LRMs).

Unlike SRMs, LRMs have guidance systems, which is just as well because they are meant to hammer a faraway target with their volleys. LRMs launcher can fire a lot of projectiles, which have little punch on their own otherwise.

It should be emphasized that LRMs and SRMs share the same hard-points. Therefore, it is possible that a Mech that is usually tricked out for long-range fire support can be modified for close-range combat in the next engagement. Indeed, the Mech can have both, for maximized versatility.

SUPPORT WEAPONS:

For lack of a better naming convention, weapons like Machine Guns (MGs), Flamers and Small Lasers are lumped under “Support Weapons”. What exactly they support is only clear if the Mechs that they are mounted on get involved in pugilistic engagements; there will be more on this later.

Anyway, support weapons are among the lightest weapons in the game. They are also among the shortest-ranged. However, they do punch above their weight, and/or can cripple their targets. Incidentally, there are some Mechs that have a lot of hard-points for support weapons, if the player desires a goofy but brutally effective close-combat Mech.

The actual use of support weapons in battle will be described later.

PARTICLE PROJECTOR CANNONS (PPCS):

Particle projector cannons are the most absurd sci-fi weapons in BattleTech lore. Even to this day, there is still no consensus among the writers of the IP over how exactly they work. Any explanation that they give is still very much incredulous and relies on near-magical and at best hypothetical technology.

Anyway, these are energy-based weapons like lasers; they do not use ammo and generate a lot of heat. However, they are designed to operate over very long distances. They do not seem to work well against anything in short or close ranges, even though they are direct-fire weapons.

The main appeal of PPCs is that they inflict the “Sensors Impaired” de-buff; the Sensor Lock ability is the only other means of inflicting this de-buff. Otherwise, there are few reasons to use PPCs, other than their very long ranges; they generate too much heat to be considered useful for any other purpose in battle.

RARE WEAPONS – FOREWORD:

In BattleTech lore, the many wars have caused the loss of a lot of technology, typically due to scorched-earth strategies or attacks on infrastructure that can support wars (directly or indirectly). Consequently, there are some weapons that are no longer in circulation in the open markets.

(These weapons happen to be more complex and more expensive than most others, so there was not a lot of interest in recovering the technology to make them.)

Interestingly, the player will rarely if not never encounter enemies that use these weapons, at least not in the vanilla version of the game.

ER LASERS:

Extended-Range (ER) Lasers inflict more damage, due to having better focus and more powerful energy output than standard lasers. However, they also have higher heat output.

The main reason to use them is in their name; the extended range moves lasers into the group of weapons that can be used over long distances, a group which is otherwise dominated by LRMs and PPCs.

ER PPCS:

ER PPCs are PPCs that have been given the same traits as ER Lasers. They enter the group of weapons that are meant to be used over extreme distances, which are usually the purview of LRMs. ER PPCs allow their users to hobble their enemies with impaired sensors even before they join the fight.

GAUSS RIFLES:

In BattleTech lore, unlike the other rare weapons, the Gauss Rifles are a category of weapons unto their own. After all, the other rare weapons are modifications of otherwise reliable standardized mechanisms.

The Gauss Rifles fire slivers of metal over incredible distances at incredible speeds; the impact is tremendous. They generate noticeably more heat than other ballistic weapons, but their damage-to-heat ratio is still far higher than any laser or PPC, or even LRMs for that matter. Hence, this is the main appeal of Gauss Rifles; long-range punishment with little heat in return.

However, misses are very costly; Gauss ammo is surprisingly precious, apparently because very few alloys can withstand the rigors of being launched out of the weapons. Gauss rifles are also the biggest and heaviest weapons around, challenging even AC/20’s for the spot of being among the most massive Mech-mounted weapons. (Actually, in-universe, that spot belongs to the Long Tom artillery.)

WEAPON QUALITY:

In addition to weapon types, there is weapon quality. Each weapon has different models, associated with different manufacturers. The models with better quality are more expensive and rarer in supply, of course. (For the sake of convenience, these models have been marked in-game with “+” symbols – to the chagrin of Battletech purists who prefer the model names.)

The number of “+” symbols are rough estimates though; the player will want to check the specifics of the higher-quality models to determine what bonuses that they have.

The bonuses are fixed according to the models; the player should not expect procedural generation of bonuses a la the system in looter-shooter or hack-n-slash titles. This is due to emphasis on gameplay balance (even for the single-player portion).

On the other hand, coupled with the limitation on the number of Mechs that can be fielded, this also means that the player would eventually hit a limit in power progression in his/her playthrough.

HEAT SINKS:

All Mechs have innate heat dissipation, but this is generally not enough for the weapons that it would pack (unless it is a Star League-era Mech). Thus, there are heat sinks that can be installed for supplementary heat management. Each heat sink removes heat by a specific amount over every turn; generally, this amount cannot be buffed.

Heat sinks may be small in size and weight, but multiples of them can stack up to considerable tonnage, especially for Mech builds that have a lot more energy-weapons than is wise.

There are not many variants of heat sinks. There is the standard and common version of the heat sink. Next, there is the Star League-era double heat sink, which takes up two more slots for double the amount of heat dissipation, but no additional tonnage.

ODD WORK-AROUND FOR GETTING DOUBLE HEAT SINKS:

The latter kind of heat sinks are never on sale; they are considered as extinct technology (“lostech”, to use the in-universe term). However, they can be obtained by cobbling together salvage of Star League-era Mechs (or purchasing the Mechs outright if the player is ridiculously rich). Then, the player fishes the components out of them. This works, but it can seem clumsy.

HEAT EXCHANGERS AND HEAT BANKS:

Heat Exchangers reduce the amount of heat that is generated by weapons; this is very useful for Mech builds that have more weapons than sense. Heat Exchangers weigh at least two tons each, however.

As mentioned earlier, Heat Banks increase overheating thresholds and heat capacity. Heat Banks weigh only one ton, but take up many slots.

AMMO BINS:

Ballistic weapons draw their rounds from ammo bins, which take up space and tonnage.

Amusingly, ammo bins can be installed anywhere on the Mech – including even in ridiculous locations. For example, weapons have to be mounted on the arms or torso sections, but ammo bins can be installed in the legs or even the head. (The latter choice is especially silly and unwise – both in the lore and in gameplay.) Interestingly, this option is there in the table-top game too.

There is no explanation as to how ammunition can be somehow transferred from the leg to the arms.

That said, the reason for this is expedience and risk in gameplay. Legs with ammo bins are more prone to being blown off if their armor has been stripped off, for example. Cockpits with ammo bins that are breached are more than likely to be fatal to the pilot.

There will be more explanation on the risks posed by ammo bins in battle later.

HALF-BINS FOR MG AMMO:

For most ballistic weapons, there is only one type of ammo bin for each of them. However, in the case of machine guns, there are two types: the usual one-ton bin, and the half-ton bin with half of its usual ammo amount. The latter will be quite helpful in filling out the last fractions of the remaining tonnage in a Mech.

JUMP JETS:

That Mechs are actually a lot lighter than they look is (somewhat) proven through the usage of Jump Jets, which can launch Mechs into the air. Jump Jets can only be installed on the legs and torso sections of a Mech, which is sensible.

Jump Jets considerably improve the mobility of Mechs, allowing them to climb hills (as dangerous as this would seem) and land on top of buildings that can support their weight (which is even more foolhardy).

Speaking of which, there are three types of Jump Jets, each of which is associated with a certain weight range. The “standard type” is for Mechs of 55 tons or lighter. The “heavy” type is for Mechs of 60 to 85 tons. The “assault” type is for the heaviest of Mechs. The Jump Jets for heavier Mechs have higher tonnage, thus posing a dilemma between having tonnage for jump jets and having it for other components.

However, considering the options that Jump Jets offer during fights and outside them, having Jump Jets is very much recommended, if not necessary.

COCKPIT MODS:

Cockpit mods can only be installed in the heads of Mechs. In the official build of the game, there are several of these.

The simply-named “Cockpit Mod” increases the pilot’s ability to resist injury due to hits on the head (or head-equivalent) of the Mech. Unfortunately, the presence of this mod in the game is indicative of a fickle problem in the gameplay; this will be elaborated on later.

There is the Rangefinder, which increases the viewing range of the Mech. Being able to see further makes long-ranged weapons easier to use without having to resort to indirect fire (more on this later).

Perhaps the most useful cockpit mods are the Communications Systems. These increase the Resolve gain rate of the entire team; Resolve is a major element in battle, and will be described further later.

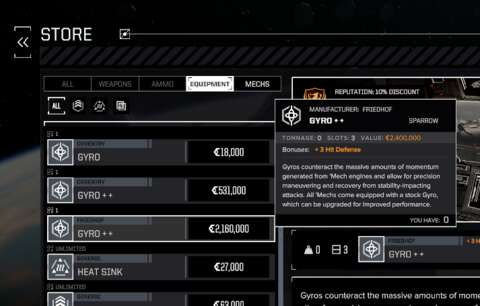

GYRO MODS:

Gyro mods generally have zero tonnage, because they are actually modifications of the skeletons of Mech chases. They can only be installed in the center torso, and they take up enough slots to prevent the installation of just about anything else in that section.

There are three types of gyro mods. The first reduces stability damage from landed hits, which in turn make a Mech harder to topple. The second increases the chances of melee attacks landing. The third makes attacks more difficult to land on a Mech.

The wise player would likely go for the third type of Gyro, if only to increase the survivability of the Mech.

TARGETING SYSTEMS:

Next, there are targeting systems. Each system mentions which category of weaponry that it is associated with. Any weapon that is mounted on that Mech that is in that category has its hit chances improved.

Targeting systems are unbelievably heavy things: they weigh at least one ton. They can also be installed in any section, including either leg. These peculiarities are likely for gameplay balancing.

ARM MODS:

Arm mods can only go into the arms of the Mechs. These increase the potency of their melee attacks. More powerful arm mods are heavier and bigger, apparently so in order to balance against the bonuses that they give.

It does not matter which limb that a Mech uses to attack with, by the way; the bonus from the Arm Mods are still applied, if they are still around.

LEG MODS:

The least of the equipment items is the Leg Mod. This reduces the damage that is inflicted on the Mech that is performing a Death from Above attack (more on this kind of attacks later). There are very few reasons to resort to Death from Above attacks, however, so these mods are not as useful as one would think.

ARMOR:

The last yet perhaps most important aspect of a Mech is its armor. There will be more on armor later, but it should suffice to say for now that the amount of armor on a Mech is proportional to its overall durability.

Armor does have weight, so the player will want to consider balancing durability with firepower – at least for Skirmish mode. In Career mode, survivability is far more important than any other aspect of the player’s Mechs.

Firstly, this is because armor replacements are “free”. A character in the story campaign even mentions that there is enough scrap metal around to be shaped and formed into armor. This explains the cheapness of armor, but the process is also quick too; this is not so well-explained.

(In the setting of the Rimward Periphery and the mid-3020s, perhaps this is appropriate; quality and made-to-design armor is rare in this setting, in which people have to make do with what they have. In other settings, especially the ones used in the table-top game, armor replacements actually come with costs and take time to be replaced.)

Secondly, armor is the ablative layer that must be stripped away before the more fragile parts of a Mech can be damaged. The fragile bits – its internals and components – take time and money to be repaired (or worse, replaced), if they are harmed. These repairs also incur downtime between missions, further stacking wasted time and opportunities to the costs that have already been incurred.

Therefore, having lots of armor would minimize downtime by preventing repairs for internals – something that is definitely beneficial to the long-term gameplay in Career mode and the story campaign.

PARTIAL SALVAGE:

In BattleTech lore, many means of producing Mechs have been lost to wars, especially that involve wholesale targeting of infrastructure and factories. However, Mechs have also been designed to be rather durable; a few parts can survive even the worst mangling and burning of a Mech. Hence, there is the secondary economy of salvaging wreckage.

In-game, the salvaged stuff from Mechs is implemented as units of “partial salvage”. Each unit of partial salvage is associated with a Mech model (emphasis on “model”). In order to cobble together a Mech of a particular model, the player needs to find enough units of partial salvage for that model. By default, this is three. (Some players who want greater challenge have complained that this is a low threshold, which in turn allows the lucky player to gain heavier Mechs earlier than they should.)

When a Mech is cobbled together, it goes into one of the cubicles in the Mech Bays. If there is no space, the player is prompted to either send the Mech into storage, or send one of the existing ones into storage. Either way, this is not convenient, especially if the player wants to have work done on the ‘new’ Mech while also retaining any Mechs that are already battle-ready.

COBBLED-TOGETHER MECHS HAVE STOCK COMPONENTS:

In addition to getting a Mech chassis from completed salvage, the Mech also comes with its stock components.

For most of the gameplay in Career mode, this is insignificant. In the case of standard Mech models, the stock components are not likely to excite the player much, especially if the player has been collecting higher-quality ones. Indeed, the player would likely just strip them off and replace them with something else.

However, in the case of Star League-era Mechs, the player would be fishing out the rare components from them, even if the player is not interested in the chassis itself (especially if the player is already fielding heavier Mechs).

REPAIRS AND REPLACEMENTS:

A Mech can suffer damage such that its components are damaged. Damaged components can be restored, fortunately, but for a cost. Costlier components typically cost more and take longer to be repaired.

However, if a component is destroyed, it has to be removed; this incurs cost, just like the removal of any working component. There is a feature to replace the component, but this is only there for user convenience; the replacement can only happen if the player has a spare of the exact same component.

BATTLE SYSTEM – PRAISES:

The following sections are mostly positive statements on the sophistication and complexity of the battles in this game. There will be some gripes in between these praising statements, but these would be minor complaints that can be waved away. The more serious problems will be described in their own sections later in this article.

HEXES AND PLANES:

The battlefield and the combatants may have 3D modelling and sculpturing, but in actual gameplay, they are occupying flat planes of hexagonal grids. These planes and grids make up the pseudo 3-D battlefield.

Therefore, each combatant has six facings. Consequently, each combatant can only be surrounded by six others; this is important to keep in mind when mobbing enemies in melee (though of course the player only has four playable units).

LIMITED VERTICALITY:

Although height is a factor in the battlefield, there is no true spatial verticality. To elaborate, a unit can occupy a hex cell in one of the planes of hexes, but the hex cells in other vertical planes cannot be occupied by others.

In other words, the player will never see a Mech standing directly below another. Indeed, there are no structures like fly-overs that would allow this occurrence. Even natural terrain like overhanging cliffs are omitted from this game so that this cannot happen.

CIRCULAR RANGES:

Interestingly, sensor and weapon ranges are implemented as circular variables, instead of hex variables. This is not unlike what has been done in the XCOM remakes.

To elaborate, a unit projects its sensor and weapon ranges in circles that are centred on it. Any hex cell that is completely within this circle is considered as within the ranges of the sensors and weapons. Any hex cell at the peripheries of the circles must have its area covered by more than half within the circle for the cell to be considered within range.

Any unit that is occupying a cell that is within range is considered to be in range of the sensors and weapons too. The size of the unit does not matter in this regard (though it does not matter in determining line of sight, which will be described later).

MOVEMENT:

Tactical turn-based gameplay in an actual battlefield with terrain more often than not emphasizes positioning as a major factor in strategies. In turn, positioning requires movement. How a Mech can move about would consequently determine what options that it can derive from its mobility.

All Mechs can walk and sprint. Their movement distances are measured in terms of hexes, which has been described earlier. Typically, lighter Mechs can move further for either mode of movement.

Obviously, having both legs would be optimal for moving about. Losing one leg prevents any sprinting; walking distances are not affected.

Losing both legs puts a Mech out of commission, even if the pilot is still conscious and the Mech still has working arms. (Interestingly, the table-top game does have rules that allow for a Mech without functional legs to continue operating, albeit it can no longer move from where it is.)

WALK & SHOOT (& SHOOT & WALK):

A Mech can walk up to the maximum distance where its movement still counts as walking, and still be able to fire its guns. This does not affect its accuracy.

Firing weapons end the turn of a Mech. However, Mechwarriors with the Ace Pilot skill can shoot first, and then walk. This is mostly useful if the Mech’s initial position is more useful for making shots.

SPRINTING:

In lieu of making any shooting attacks, the player can choose to have a Mech sprint instead. This lets the Mech move across longer distances, and gain more evasion charges (more on these later). However, sprinting away from battle would expose the Mech’s back to enemies, so this is not always a good method of putting distance between oneself and enemies.

TURNING:

In lieu of moving, a Mech can turn in place. In this case, the Mech can turn around any number of degrees and along any arc. Of course, a Mech that stays in place is very much an easy target.

A Mech can still turn after moving. However, the amount of turning that can be done depends on the distance moved and the number of turns that have been made along the path. Longer distances and more turns before stopping leads to smaller arcs of turning at the destination. This is the reason for the aforementioned statement about the risk of sprinting away from battle.

Jet-jumping allows a Mech to turn to any facing, as if it has not moved at all. This makes Jump-Jets incredibly useful for changing the facing of Mechs while also moving, but this comes with a price, of course.

JUMPING:

Speaking of Jump Jets, these allow Mechs to move over obstacles in their path, such as walls and sheer cliff faces. The height of the jump does not matter in the gameplay; only the horizontal distance appears to matter. (Indeed, in some circumstances, Mechs can jump ridiculously high.) Jumping is also useful in battle, due to the aforementioned convenience of changing a Mech’s facing.

Another appeal of jumping is that it is not affected by terrain limitations. (Terrain effects will be described later.) Furthermore, landing is not an issue, regardless of how precarious the Mech’s landing spot is. (In the table-top game, players are required to make rolls against their pilots’ skills if they land on tricky places.)

However, jumping generates heat, as is to be expected of rocket thrusters. This heat build-up is not massive, but it is considerable enough to make shooting guns after jumping riskier than not jumping in the first place.

BRACING:

When a Mech is not able to do much other than walk in its own turn, its only remaining option is to brace. Bracing ends its turn immediately, but grants it the Entrenched and Guarded status; these will be described later.

There are few reasons to brace, especially considering that the Vigilance ability does what it does without ending the Mech’s turn. (Vigilance will be described later.)

ARMOR, AGAIN:

Armor is the first layer of “hit-points” that Mechs have, to use a video game term. When kitting out a Mech, the player can choose the amount of armor that would be in each body section; this is the amount of armor that the Mech would have at the start of the mission.

Armor cannot be replaced during battle in this game (and in the table-top game), unlike the MechCommander titles. Therefore, the player will want to utilize strategies about keeping damage to a minimum.

As for the amounts of armor that a Mech can have, they appear to be dependent on its weight rating, instead of its chassis type and model. Indeed, for example, the King Crab and the Atlas – both 100-ton Mechs – have the same armor capacities. There is a wasted opportunity to further differentiate Mech chases here, but the simplification also keeps gameplay balance between Mechs in check.

REAR SECTIONS:

The rear sections of a Mech are connected to the torso sections on its front facing. For (not-always believable) engineering reasons, the rear sections of the Mech have much thinner armor and weaker internals (more on these shortly).

(BattleTech lore has tried to explain this away as part of the heat dissipation quirks of a Mech and/or easy access to its spine and reactor. However, players who are educated mechanical engineers and technicians might notice that their rears do not always have things resembling heat dissipating elements or access panels.)

Anyway, the rear sections are not to be considered as additional sections. If any of these sections is destroyed, the front section that is connected to it is automatically destroyed too. This happens regardless of any remaining armor and internals that the front section still has.

Furthermore, any attacks that land on rear sections bypass any defences borne from the pilot’s skills; bonuses from cover still applies, unless the attacker is using Breaching Shot (more on this later).

Therefore, it is important for the player to prevent the rear arcs of his/her Mechs from coming under fire. Unless, of course, the front sections had been so badly mauled that it may be wiser to have the rear arcs facing the enemy instead.

HITS ON LIMBS:

The limbs of a Mech have no front or rear sections. If they are hit from the rear or front, all damage is applied to the same meter. However, as mentioned earlier, hits on the rear bypass skill-derived protection, so it is easier to damage limbs from the rear.

INTERNALS:

After armor has been carved away from a section, the internals of that section are now vulnerable. When this happens, the initially grey section of a Mech’s “life-bar” becomes orange.

The integrity of internals is represented in the same way as that for armor, i.e. a meter. Like armor, internal meters are on a one-way trip to zero.

DAMAGE TO COMPONENTS IN SECTIONS:

As the internal meter depletes from further hits, the game starts rolling RNGs for component damage. Any component in the affected section is at risk of being damaged; components with the most slots occupied are likely to suffer first.

Moreover, there are high-quality weapons whose bonuses are improved “critical” chances, which translate to greater likelihood of components being damaged when they land hits on exposed internals.

Damaged components have poorer performance. Considering how fickle the RNGs in this game can be, it is not in the player’s interest for this to happen to his/her Mechs.

COMPONENTS BEING DESTROYED:

Damaged components that are damaged again through the aforementioned RNG rolls are destroyed. Furthermore, as the internal meter depletes, components are certain to be destroyed. Again, bigger components go first, because they are assumed to take up the most space in that section and thus is the most vulnerable. Of course, if that section is completely trashed, all of the components there go with it.

Destroyed components definitely no longer function, and cannot be potential salvage in the case of components on enemy units.

AMMO BIN EXPLOSIONS:

Ammo bins that are destroyed automatically detonate if they have ammo left. The detonation will inflict further damage on the internals of the sections that they are in, possibly causing a cascade of ammo explosions that destroy the Mech and/or kill the pilot.

The amount of damage that is inflicted depends on the amount of ammo remaining. The exact equations are unclear, however. Still, there is the certainty that empty ammo bins do not explode.

That said, damage from ammo bin explosions inflict damage to internals. The damage is first applied to the section that the bins were in, and then to any adjacent body section if there is excess damage.

This happens as per the mechanism of damage overflow; see the next passage. However, there is one exception: the damage from ammo bin explosions always goes to internals; armor is not affected. This damage can harm components on the other body sections too – including other ammo bins.

DAMAGE OVERFLOW:

If a limb is destroyed from hits, any excess damage that the limb’s armor and internals did not absorb is applied to the next adjacent section. Armor is affected first.

In the case of legs, this goes to the center torso. In the case of arms, this goes to the left or right torso sections, whichever pertinent. This is told to the new player through a loading screen tip, however, so this might be missed if load times are very short for the player.

If the left or right torso section is destroyed, excess damage is transferred to the centre torso section. Any arm that was still attached to that section is automatically torn off too. However, the components in the torn arm are intact, if they have not been damaged earlier.

Excess damage does not flow from destroyed centre torso sections and heads, however. There is no reason to implement this anyway; the Mechs are already knocked out.

CERTAIN KNOCK-OUTS:

Speaking of which, a Mech does not need to have all of its sections destroyed in order to be removed from battle. If a Mech’s centre torso section is destroyed, it is definitely out; its spine is destroyed, its reactor is disabled and such other mechanical catastrophe.

Likewise, having the head of a Mech blown off knocks out the Mech; its pilot is very much dead. However, this occurrence is a major fluke of luck, as will be elaborated in a complaint later.

ENTRENCHED:

Entrenched is one of the few buffs that a Mech can have. Practically, it reduces damage from landed hits. The reduction is only 25%, but considering that all Mechs are on a one-way trip to the scrap-heap in a battle, any means of reducing cumulative damage would be useful. However, Entrenched only works if the hits landed on the sides or front of the Mech.

Any existing Entrenched buff is lost if the unit has ended its turn but has not done anything to have the buff applied again.

HEAT:

Heat is the main limitation on the offensive capabilities of a Mech. Just about every weapon produces heat, which accumulates in the Mech. When enough heat has accumulated to breach its tolerance threshold, the Mech starts overheating. Overheating Mechs damage their internals rapidly over every turn that they are overheating, and there is a chance that the pilot would be harmed too.

Worst of all, if the heat has accumulated beyond the maximum tolerance of the Mech – which is higher than its overheating threshold – the Mech shuts down. Although it vents out a lot of heat while shut down, the Mech is completely vulnerable to attack; chances to hit it are often very near the maximum (more on this later).

Thus, it is in the player’s interest to manage the heat build-up of his/her Mechs. The CPU-controlled opponent certainly does keep that in mind (though it would still make gambles in certain situations).

In this game, only Mechs have to deal with heat; ground vehicles do not have this issue. Hence, ground vehicles do pose a threat if they are not dealt with early in an engagement.

SHUTTING DOWN AND STARTING UP:

A Mech that has been shut down due to severe overheating is very easy to hit, in addition to having its internals being rapidly damaged. There is otherwise no other deleterious effect.

A shut-down Mech must restart on its next turn; the player does not get to keep the Mech shut down just to take advantage of its considerable cooldown. (There is a further complaint about not being able to do this later.) However, the Mech forfeits its turn.

RECOIL:

Heat is the main limitation on firing lasers, PPCs and missiles repeatedly. Recoil is the counterpart for limiting the repeated use of autocannons and Gauss rifles.

Every firing of such a weapon causes that weapon to suffer an accuracy penalty on the next firing, if the latter is attempted in the next turn. If the latter is attempted anyway, the penalty is made worse and applied to the next firing, in the turn after.

This means that sustained firing of a ballistic weapon progressively gets more unreliable. To alleviate the penalty, the weapon should not be fired for one turn.

This limitation prevents the player from exploiting ballistic weapons, which otherwise can be fired more often than energy weapons.

STABILITY & STABILITY DAMAGE:

In addition to the durability of a Mech, there is its stability. In BattleTech lore, Mechs cannot actually stand on their own without their joints being locked; even Mechs in gantries are at risk of toppling if they are not secured.

Rather during operation, they derive their balance from their gyros. The gyros in turn depend on sensory input from the pilots through their “neurohelmets”.

This works both ways. Any hits that jolt the Mech will be felt by the pilot. Sustained pummelling eventually causes the pilot to be dazed, causing the Mech to stagger. The severity of the staggering is represented as “stability damage” in game.

(Ground vehicles are not subjected to this gameplay factor, by the way.)

Anyway, the stability meter shows the percentage of stability damage that has been taken over the total amount of stability damage that the Mech can take before adverse effects set in. If the stability meter fills to 80% and above, the Mech is rendered unsteady. Unsteady Mechs immediately lose all evasion charges (more on these later), and cannot jump or run.

If the meter turns full, the next attack that does 10% or more stability damage, relative to the meter, will cause the Mech to fall down prone. (It always falls down on its back though, i.e. its rear section will never be exposed to the enemy.) A prone Mech is automatically susceptible to Called Shots, which will be described later.

The stability meter is separated into sections, with each border representing a “threshold”. The actual capacity of a Mech to shrug off staggering is determined by the number of thresholds. In turn, the number of thresholds depends on the “Guts” skill of the pilot, which will be described later.

RECOVERING STABILITY:

Some stability damage automatically goes away by the Mech’s next turn. There does not appear to be any means of causing stability damage to be completely retained, unless the Mech has already been knocked prone (more on being prone later).

Stability damage can be completely removed by having the Mech brace, but that would end the Mech’s turn. The Vigilance ability also removes stability damage outright, making this is a better alternative.

GUARDED:

“Guarded” is one of the few temporary buffs that a Mech can have. This reduces the stability damage from landed hits, as long as they came from anywhere but the rear. “Guarded” is automatically gained if the pilot has specialized in the abilities granted by the Piloting skill (more on these later). However, the buff is lost in the next turn unless the Mech does something that grants the buff again.

BEING PRONE AND GETTING UP:

Becoming prone removes the Guarded and Entrenched buffs. This is important to keep in mind, because this is the best means of defeating an enemy Mech that has a Mechwarrior with Piloting abilities.

As mentioned earlier, being prone renders a Mech vulnerable to Called Shots. However, the Called Shots are done with penalties, due to the flattened profile of the Mech. Nonetheless, being subjected to Called Shots is bad, because most enemies will target weakened sections. Furthermore, its prone profile will not lower its visibility, even if the Mech is behind partial cover.

A prone Mech must stand up upon its next turn; there does not appear to be any way to have the Mech stay prone. Unlike restarting from a shutdown, this does not cause the Mech to lose its turn. In fact, it recovers all of its stability, it can walk around and it can even shoot. However, it cannot sprint or jump.

EVASION “CHARGES”:

When Mechs have moved sufficient distances in their turns, they gain “evasion charges”. These make the Mechs more difficult to hit with shooting attacks.

Longer distances provide more charges. This means that lighter Mechs can generally gain more charges than heavier Mechs. However, there are some weighty Mechs that are designed towards fast movement, such as the 95-ton Banshee that can outpace heavy-class Mechs.

Evasion charges reduce the probability of hitting the Mech. The charges are more effective on lighter Mechs than heavier ones, but huge Mechs like the aforementioned Banshee can still be very difficult to hit if they can amass several charges (coupled with their durability, they would indeed be difficult to bring down with gunfire).

However, every attack (ranged or melee) on a Mech with Evasion charges, whether it lands or not, will remove one charge. Thus, consecutive attempts to shoot the Mech would be easier. (Emphasis on “shoot”; melee attacks on the Mech work differently, as will be described later.)

If an attack renders Mech unsteady, it loses all of its charges. This can be devastating to Mechs that have been relying on their speed not to get hurt.

All remaining evasion charges from the previous round are also lost when a Mech takes its turn. These previous charges are replaced with whatever charges that are gained from its turn.

MELEE ATTACKS:

All Mechs can make melee attacks. Even the Mechs that do not have actual arms can make melee attacks, apparently through head-butts or an upwards shove. However, Mechs that have arms – and actual fists – are better than other Mechs in the same weight range at making melee attacks. Of course, heavier Mechs inflict more powerful attacks, by default.

Mechs that have lost limbs can still make melee attacks; however, their damage output is diminished.

The main appeal of melee attacks is that they ignore evasion charges. This means that it is possible to hit a Mech that has been amassing a lot of charges, and then remove all of them by rendering it unsteady (likely through the same melee attacks).

The other appeal is that few shooting attacks from a Mech can do as much damage as its melee attack, especially in the case of the assault Mechs (whose category name already suggests what they are best good at). Indeed, it is possible for an assault Mech to outright knock out a Mech that is one-fourth its nominal weight.

BONUS FIRING OF SUPPORT WEAPONS AFTER MELEE ATTACKS:

On their own, support weapons have short ranges that make them quite useless in most ranged engagements. Indeed, without any other quirks, there are few reasons to use support weapons.

However, they do have quirks; the greatest of these is that support weapons can be fired immediately after a melee attack, whether the attack lands or not. This adds to the harm that melee attacks can inflict. Machineguns, in particular, are well primed to exploit any vulnerability after the melee attack has stripped away armor.

Another quirk is that support weapons are very accurate – which is to be expected because they are designed to fire at targets within very close ranges.

OTHER SECONDARY DAMAGE:

Certain attacks can inflict de-buffs. The most prominent example of these is the effect of hits from PPCs. The crackling electricity from PPCs strains the target’s electronics, thus imparting the “Sensors Impaired” de-buff. This de-buff can be stacked from multiple PPC hits, though the target would not likely survive to suffer the cumulative effects of the de-buff.

Another example is the use of the Precision Strike ability on enemies (more on this ability later); this reduces the initiative step of the target, which can be tactically useful. (There will be more on initiative steps later.)

INDIRECT FIRE:

Indirect fire is about shooting at enemies that a Mech has not spotted, but its allies have. The shooter will have a penalty to its accuracy for doing this, though the penalty can be reduced by improving the pilot’s Tactics skill (more on this later).

Indirect fire is especially prominent among weapons that have “extreme” ranges; such ranges include distances close to the length/width of the map. These include ER PPCs and all LRMs. Normally, these weapons can reach things outside the viewing range and even sensor range of any Mech, but cannot fire on anything that has not been spotted by allies.

ARCING FIRE:

A unit that is armed with LRMs can fire the missiles over obstacles in between the Mech and its target. The arcing of the missiles does not count towards their range limits; the vertical travel of the missiles is not an issue. (In the official vanilla build of the game, only LRMs are capable of indirect fire.)

Indirect fire is a considerable advantage for missile-armed units. However, since there is no direct line of sight, arcing fire also automatically counts as indirect fire.

ATTACKS ON FACINGS:

When a unit makes an attack on an enemy, its attack – be it weapons-fire or melee attack – would land on a facing of the target. This facing is shown as a flashing red outline on the body section diagram of the enemy. Any sections that are encompassed by the outline are potential spots that can be hit. The ones that are not encompassed generally will not be hit.

CALLED SHOTS:

A “called shot” attack allows the owning player to have the unit to focus on a specific section. This makes that section the likeliest to be hit, though there is still a percentage threshold and RNG roll involved. There will be more on this later in a complaint about the game.

Anyway, called shots are there to give the player a chance to apply and distribute damage across the body sections of an enemy. This is usually more useful in battles that happen in Career mode than the battles in Skirmish mode, because this can help the player maximize potential salvage.

Called shots cannot be used together with melee attacks, for obvious reasons. (For one, Mechs without arms would have a hard time directing their melee attacks to specific locations.)

STRAY SHOTS:

Weapons-fire can miss the target, but missed shots are not certain to be wasted. The game rolls more RNGs for missed shots, determining whether they are “upgraded” into “stray shots”. For the rolls to happen, there have to be other units that are in the line of fire, or are adjacent to the target.

If the missed shots turn into stray shots, they visibly appear to land on the other units instead. They take the damage and stability damage from these shots, and will also lose an evasion charge if they have any.

This mechanism of stray shots cannot occur for melee attacks, also for obvious reasons.

INJURIES:

The pilots are the most important parts of the Mechs, but they are also the squishiest. Even though they are ensconced in a multi-ton war machine, they can still be wounded and killed. The amount of hurt that they can take is shown as the pips under their portraits; if they run out of these, they are incapacitated, and are at the mercy of the RNG rolls.

Firstly, any attack that lands on the head from any weapon, including even machineguns, wound the pilot outright; the pilot loses one pip. However, multiple hits on the head from the same volley will only inflict one injury at the most (though of course the head of the Mech is at risk of being destroyed).

Secondly, having the Mech fall down injures the pilot too, presumably due to being jostled around in the cockpit. It is possible to knock out a Mech by causing it to repeatedly fall down. Thirdly, the explosion of any ammo bin also wounds the pilot.

CRITICAL EXISTENCE FAILURE:

Interestingly, the amount of injuries that a pilot has sustained does not affect his/her/their performance. As long as a pilot still has one pip left, his/her/their Mech can continue to function.

INCAPACITATION:

If a pilot loses all of his/her/their pips, the pilot is incapacitated. If the centre torso of a Mech is destroyed, the pilot is also incapacitated.

In the case of the player’s pilots, their fate is determined by RNG rolls, with the outcomes being revealed in the after-action reports (more on these later).

OUTRIGHT DEAD:

If a Mech’s head is destroyed, the pilot is dead. Considering that the head section of any Mech has very little armor and internal integrity, the sudden demise of a pilot during a battle is really possible. There will be a complaint about this later.

If the Mech suffers a catastrophic “Ammo Explosion” demise, the pilot also dies.

EJECTING:

In Career mode, the player has the option of having a pilot escape a doomed Mech by ejecting. Ejection of its pilot, of course, takes a Mech out of the battle. The Mech can be recovered later, regardless of the circumstances of the outcome of the mission.

Ejecting is only useful in Career mode. In Skirmish battles, there are few reasons to not have a badly wounded pilot or badly damaged Mech to just keep fighting.

TERRAIN - FOREWORD:

Terrain is an important element of battles. In Career mode, the player’s lance is always outnumbered; terrain helps in limiting the number of enemies that can attack them. In Skirmish battles, terrain can provide a major advantage (or disadvantage) against the otherwise equally powerful opponent.

There are also several aspects to terrain. Each of these is visually represented on the battlefield, sometimes in silly ways.

REGULAR GROUND:

The bulk of terrain is regular ground. This imparts no bonuses or advantages, unless there are differences in elevation, which will be described shortly.

ELEVATION DIFFERENCES: