INTRO:

The Cold War may not have escalated to actual military conflicts, but there were enough advancements (if they can be called as such) in intelligence-gathering and counter-intelligence operations that would put chills in spines.

A game developer thought that such a setting would be great for a video game. Gameplay-wise, they did mostly a good job. However, it would soon be clear that their design policies do not really contribute much to the design of a good narrative.

PREMISE:

The game is set during the zenith of the Cold War, when clandestine and sometimes macabre covert operations were taking place (according to various de-classified information and the imagination of conspiracy theorists).

Prior to the beginning of the playthrough, the player selects the initial allegiance of the main player character. The story begins with the main player character leading a small counter-intelligence cell, ferreting out traitors, double agents and corrupt officials independently of official intelligence agencies. The first few missions take place in the homeland of the main player character, as befitting his/her original job description.

Eventually, the main player character uncovers signs of a global conspiratorial group that is attempting to turn the Cold War into a real war. The main player character decides to go global, and gave the callsign “Cabal” to his/her expanded counter-intelligence group.

This is when the different origin stories converge into the overall plotline. The origins of the main player character are also soon made unimportant, due to a certain plot twist that experienced followers of fiction might already see coming.

What happens after is more spy-craft, albeit on an increasingly global scale. The player’s group would have to expand considerably, bringing in more expertise but also introducing more vulnerability to infiltration. Still, eventually, the player would run the conspiratorial group to the ground, and discover their motives and co-conspirators.

ORIGINS:

One of the game’s elements is the origins of the agents in the Cabal, including the main player character. In the case of the main player character, this determines the identities of two persons that matter in the story (one of whom is the main player character). Each origin also determines which set of introductory missions would be used at the beginning of a playthrough.

Thus, the origins of the agents have little more significance than a gameplay gimmick. The origins determine their starting skills and weapons training, but that is it.

THE CABAL:

The awkwardly named “Cabal” is the collective of agents that have been recruited to oppose the aforementioned global conspiratorial group.

The Cabal starts out small, with only basic amenities to support the agents. Indeed, due to their clandestine nature, they have to operate from what appear to be abandoned or derelict buildings. Their rooms are in the interiors of buildings, with any rooms that happen to have windows having these all boarded-up or shuttered to minimize the risk of being observed.

Fortunately, the hour-to-hour operation of the Cabal has been simplified so that the player does not have to worry about curious people stumbling into their headquarters or lodgings. Indeed, there are next to no random events about these that would inconvenience the player. (There are still some factors of luck, which will be described later.)

For the Cabal to operate well, it must have agents. The agents are there to gather information and participate in missions. Agents can also be set on more menial tasks at the Cabal headquarters, like forging money (none of its activities are actually legal) and crafting (very illegal) equipment like lockpicks.

As much as the Cabal is going after its enemy, its enemy is also going after it. The player has to keep the Cabal’s headquarters and agents safe, which is easier said than done. Fortunately, the factors of doing so are almost all within the control of the player, or at least the player can monitor them.

That is about the defence of the Cabal. Ultimately, the Cabal has to go on the offensive to inflict any damage to the enemy. Most of these decisive measures are initiated through missions, in which the player must actively play.

In the long term, the player has to manage the Cabal’s finances and resources – the former in particular. Many things require money, something that the Cabal does not have in spades because it is not officially sponsored by any governments or other major organizations. (Indeed, it may even be funnelling funds from them.) One of the worst ways to fail is not having enough money to relocate after the headquarters’ location has been compromised.

BEHOLDERS:

For ease of reference, the global conspiratorial group that the Cabal would oppose would henceforth be referred to as the “Beholder Initiative”, as they are called in-game, or “Beholders”, for short. This is a spoiler, but referring to them as the “opposing global conspiratorial group” would be terribly inconvenient. Besides, the gameplay designs of Phantom Doctrine would already refer to them as the “Beholder Initiative” prior to the reveal of their name in the narrative progression.

The Beholders’ resources are vast; the progression of the story would reveal that they had been working behind the scenes of those working behind the scenes. Their motives and how they got together would only be revealed much later in the playthrough

Yet, it would be clear soon that they have what other intelligence and counter-intelligence groups have. Indeed, the Cabal would be expanding its capabilities by stealing from the Beholder Initiative. The hypocrisy and irony of resorting to the Beholders’ own nasty methods would be deliberately hand-waved away.

For example, the same character that suggested burning a Beholder facility to the ground would remark on how gratifying it would be to use the Beholders’ mind-bending techniques on their own operatives and collaborators.

Despite the setbacks that the Cabal would inflict on the Beholders, the Beholders would hardly be impeded; the most that the player could do is to stall them, at least until they could discover their most daring plans. The narrative reason for this is that the Beholders are just too vast and well-resourced to take down with continuous disruptions of their operations and neutralizations of their agents.

Gameplay-wise, it means that the player would be dealing with unending waves of enemy agents that are trying to nail the Cabal and its assets, no matter how many of their own cells have been destroyed and how many of their agents have been captured and eliminated. Yet, dealing with these would take up much of the player’s time in any playthrough, possibly to the point of becoming boring.

RECRUITING AGENTS:

The main player character is a skilled agent, and he/she has a few colleagues already. However, as the Cabal expands its operations to many places across the globe, it will need more manpower.

It takes a special person to give up his/her original identity in order to take on the career of an intelligence/counter-intelligence operative. However, the motivations and effort of convincing them to join have been simplified to just shelling out money to recruit an agent with no questions asked. As for the potential list of recruits, entries in the list are updated as part of the “rewards” for having completed missions and collecting intel.

The list only ever has five persons. If the player comes across any intel for potential recruits, the existing entries in the list are replaced with these, which tend to be a bit better. Indeed, as the playthrough progresses, the minimum level of potential recruits rises.

After an agent has been recruited, the list can only be updated by finding more intel on potential recruits. This is usually not an issue, because potential recruits are the default for any rewards if the game does not consider other rewards to be appropriate.

Managing the recruits afterwards is a different matter, however. Each agent is a great asset, but he/she is also a risk, especially the agents with hidden traits. Rotation of agents from one task to another is also something that the player should do frequently, due to the mechanism of “heat” that will be described later.

MONEY:

The other resource that is important to the Cabal is money. Unlike most other tactical turn-based games that are based on XCOM, money is always in short supply throughout most of the playthrough, because a lot of money has to be periodically consumed to maintain the Cabal’s safety.

The Cabal automatically gets some money from unspecified sources. This funding is small, but steady. To get more money on a steady basis, the player needs to place agents in the forgery (after it has been set up) to forge more money. Forging money does not grant any experience points, however, so the player might want to rotate agents into and out of forgery.

Ultimately though, the steady sources of money are just too small if the player intends to fast-track the upgrading of the Cabal’s capabilities. Yet, for a group that engages in so many illegal activities, stealing money is not one of them. Instead, the player would be stealing hardware, especially guns, and selling spares of them on the black market.

AGENT STATISTICS:

For better or worse, every agent has two sets of statistics. One set, which is the primary statistics, would be familiar to followers of D&D-like RPGs; they govern the numbers that go into the second set of statistics.

The second set of statistics is what actually matters in the gameplay. These include staples of tactical turn-based gameplay such as hit points, armor and movement distance. To be specific, Phantom Doctrine is using the system that the XCOM reboot has established, so followers of the system that Firaxis has popularized would find most of them to be familiar. However, there are some notably different designs, namely the statistic of Awareness and the lack of RNG-based accuracy factors.

The exact interaction of the primary statistics with each other and how they determine the second set is not documented thoroughly in-game. There are only brief tool-tips that say which statistic depends on which statistic.

BODY ENGINEERING:

The main and perhaps only reason for the implementation of the primary set of statistics is the “Body Engineering” facility and its services. The player obtains this facility a short while into the playthrough. It lets the player treat the bodies of his/her agents with chemicals, some of which are based on real-world chemicals with alarming properties (like Bolasterone).

These one-time-only treatments enhance an agent’s primary set of statistics, while possibly stymying a few others. The player can see the changes in the primary set of statistics as well as the changes in the secondary set. However, for whatever reason, the developers forgot to include the option to de-select any option so that the player can see the agent’s original statistics.

Not all of the chemicals are available from the start. Rather, the player finds them among the rewards for having stolen enemy assets or gathered intel. After obtaining them, applying them is a relatively simple matter: they do not take long to apply, and they do not cost a lot.

However, some chemicals prevent the application of other chemicals. This restriction was implemented to not only mirror real-life restrictions on consumption of chemicals, but to prevent players from making ridiculously-buffed agents too.

CITIES:

For better or worse, almost of the gameplay occurs in cities; there are rarely any other kind of locale that the player would be seeing.

Nevertheless, any city is a large location with many places. Therefore, the player would be infiltrating into locations with man-made edifices and facilities, such as office buildings and train stations. All of these locations will also have considerable numbers of civilians and guards, in addition to the player’s targets.

Generally, there is one disturbance, opportunity or mission in any city at any time. However, it is possible for a city to host two missions, in which case the user interface that list the missions would accommodate their presence. However, the world map view does not reliably show the presence of multiple missions in the same city.

AIR TRAVEL:

Although the Cabal has limited monies, they have the convenience of unlimited air travel, peculiarly enough. Perhaps this was implemented in order to streamline the gameplay, but it does go against the notion of having limited funds.

Anyway, air travel is the only way that the Cabal’s agents would use to move from city to city. This allows them to reach almost any city within one day or less. However, many events can happen within a day, so shorter travel times are always better. Strangely enough, the Cabal can gain upgrades that somehow reduce air travel time. (Presumably the agents are getting access to more prompt flight schedules, but that is not exactly the best explanation for the overall reduced travel times.)

There does not seem to be any limitation to air travel. For example, there is no grounding of flights due to bad weather. Furthermore, as powerful as they are, the Beholders do not have the influence to delay or cancel flights. Plane crashes or flight diversions also do not occur. All these conveniences mean that travelling is mainly one of the factors that the player has to consider when maximizing the productivity of agents.

ENEMY AGENTS IN WORLD MAP:

Enemy agents are periodically spawned into the world, and each will undertake operations against the Cabal. It is possible for the player to eliminate all extant enemy agents and enjoy a brief period of safety, but they are always coming.

Initially, the number of enemy agents actively opposing the Cabal can number from merely two to more than half a dozen if the player has not been winnowing them. If the player has reached certain milestones in the playthrough, more are spawned when the next story development comes up, and the ceiling number of extant enemy agents rise further. Indeed, the playthrough’s success will be dependent on the player constantly catching and removing enemy agents from the picture.

All enemy agents initially appear unidentified and undiscovered; the latter circumstance is more worrisome. However, it is generally quite easy to discover their existence, mainly because almost every mission would have at least one enemy agent. If there are not any extant enemy agents for an important story-advancing mission, the game spawns at least two for that mission.

Unidentified enemy agents have the advantage of having their capabilities obscured from the player. However, the player can eventually gain information on them, assuming that the player would not already be getting rid of them during missions. Encountering enemy agents during missions reveals a bit more about them, and information on them can be found among rewards.

Eventually, an enemy agent would be so well identified that whatever they are doing at the time is known to the player. Most importantly, the player can now have his/her own agents track them down so that they can be eliminated one by one.

Until that happens, the enemy agents will carry out activities that can screw over the Cabal. The worst of these is the locating of the Cabal’s headquarters. Another bad thing is the consequence of any counter-intelligence operation that they are carrying out in a city; any agent that is in that city is at risk of being caught.

HEADQUARTERS OPERATIONS:

Most agents would be operating away from the headquarters, but the headquarters have facilities that let them do some things that would not be safe to do elsewhere.

The most important of these is recuperation. Some missions can go sideways, and some can even go that way right from the get-go. When that happens, it is rare for agents not to get injured. Any injuries that they still have at the end of a mission is carried over into the world map, and they will not regain this health automatically while they are still in the world map. To regain health, they need to rest in the infirmary.

Then there is the aforementioned forging of money. It is likely to be the very first facility that the player would build, and would likely be staffed permanently (preferably on rotational basis).

Tools for spies are scarce, even with black market contacts. To make these tools, the player needs to have a workshop at the headquarters and the schematics for them. Then, agents have to be assigned to their crafting. (It’s the 1970s, prior to the advent of conveniently automated manufacturing.)

TRAINING:

The headquarters are also where agents receive training, after they have become eligible to have it (typically after having gained some levels). It is not clear who is training them, and they are somehow able to complete the training under two days (though two days is a long in-game time).

Training costs some money, but the real cost is that the agent is unusable until after he/she has completed the training. Indeed, the player would be having worries about this; the agents need the training in order to become more competent, but the player would be having manpower troubles.

Incidentally, there is no limit to the number of agents that can go on training at any time. This contrasts with the limited slots in the facilities at the headquarters. Again, this difference is likely there to emphasize the disadvantage of the relatively long training times.

Each training module generally has two sets of benefits. The first set is proficiency in certain weapons; weapon proficiencies will be described later. The second set is an ability that can be activated during a mission, or an ability that imparts a passive benefit. The second set is usually more desirable than the first set, because it is usable for stealthy gameplay too.

PERKS:

Unlike training modules, perk gains can be applied on agents immediately and without any cost or fuss. However, perks only grant passive bonuses; they do not introduce any new ability. Many of them are situational too. For example, perks that improve disguises only confer their benefits if the agents are disguised, but not every agent can be disguised in a mission.

Nevertheless, there are some perks that would provide benefits to any situation. Chief of these is the perk that increases maximum health. Incidentally, maximum health is of great importance in takedowns, which will be described later.

TALENTS:

Perks are traits that agents gain as they level up. However, they may already have traits prior to gaining any levels; these are called “Talents”, and coloured green instead of blue.

Not all Talents are revealed to the player from the get-go. If they happen to be beneficial, they usually impart benefits that make it easier for them to do things at the headquarters. For example, there is the Talent that reduces the time for Body Engineering processes to be applied on agents.

If they happen to be negative, they tend to be proof that the agents had been double agents that the Beholder Initiative has planted. These “Talents” are devastatingly detrimental when they come into play. This will be described shortly later.

Hidden Talents are not easy to expose. They may be part of rewards from intel-gathering, but these are rare. The player can develop another agent to reveal the hidden Talents of other agents, but this comes with considerable opportunity costs, and having to have this agent on missions might not be a wise choice all the time.

DOUBLE AGENTS:

Not long into the playthrough, the Beholder Initiative is revealed to be quite fond of science and technology that mess with the minds of people. One of the things that they can do is capture agents, mind-screw them, and let them go back to the Cabal. The Beholders also regularly make available recruitment candidates that are already compromised.

Incidentally, the hidden Talents of agents may turn out to be evidence of brain-screwing. If so, the agents become severe liabilities. For example, the most common detrimental “Talent” is “Sleeper Agent”, which turns the agent into an enemy when the alarm is raised during a mission.

Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to address this problem as early as possible. In the progression of the story, this is achieved through the “MKULTRA” facility, which will be described later.

SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITIES:

The Cabal and its agents are not working alone. Presumably, each agent brings his/her network of friends and contacts into the Cabal too. For one, the main player character would reveal that he/she has a considerable web of pals.

It is likely that these friends and contacts are the ones warning the Cabal about peculiar activities in the cities; how they somehow catch wind of these is glossed over in the gameplay of Phantom Doctrine.

These “suspicious activities” may or may not be false alarms. If they are not, they either reveal enemy activity or a benefit for the Cabal; there will be more on the latter later. Which they are happens to be determined with an RNG roll that is made when the agents arrive at the cities. Fortunately, this is not entirely out of the player’s control; there are options to improve the chances of these suspicious activities being beneficial.

AGENT BAGGAGE:

Each agent, when they are recruited, is assigned a backstory of sorts. This backstory will determine the kinds of events that would occasionally pop up; these events concern their welfare, any baggage from their past, or their aspirations. The player is given some options to resolve these events; all of them are mutually exclusive.

This is where fickle luck can rear its ugly head. Generally, the options that require the player to spend money has the best outcomes, but the player may get the least bad outcomes from them instead. If the player is terribly unlucky after choosing options that do not cost anything, the player loses the agent, or the agent even defects. If the player is lucky, the agent becomes loyal and will no longer be involved in further incidents.

MISSION TIME WINDOWS:

When suspicious activities turn out to be those of the Beholders, the player is shown the missions that can be carried out against these enemy operations. Each of these missions has a time window, during which the mission can be carried out. If the time window counts down to zero, that mission can no longer be carried out because that Beholder activity has progressed too far for that countermeasure.

Furthermore, if the suspicious activities are uncovered later rather than sooner, the Beholders would already have a headstart, counting from when the warning of suspicious activities was given. Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to investigate suspicious activities whenever they occur.

NOT-MISSION MISSIONS:

For better or worse, the game does not clearly label or typify the missions that agents can undertake against Beholder operations. There are two overarching categories of missions. One category has the agents carrying out tasks over time, without the need for the player to mind them. The other category of missions invoke the other major portion of Phantom Doctrine’s gameplay, that of tactical turn-based scenarios.

The first category often requires two or more agents. For example, Tactical Recon requires at least two agents. However, not all of the missions in this category are available from the get-go. Rather, they have to be unlocked through R&D options at the workshop of the headquarters.

The first category of missions gives a bit of experience points; the amounts become relatively unrewarding later in the playthrough. Talents that increase XP gains from these missions also become just as worthless.

TACTICAL RECON:

As mentioned earlier, cities are large places. The agents may not be familiar with every location in any city, and even if they do, their enemies would have taken measures to secure their places of operation.

Therefore, prior to any mission against the Beholders in any city, the player can have agents scout out the mission location. Presumably, they also prepare the grounds around the mission location and clothes for disguises during this time.

Indeed, if the player does not carry out tactical recon for a mission location, the agents have to go on the actual mission practically blind. The map is covered in fog of war, thus obscuring the layout of the mission area and the locations of any objects of interest (more on these later). The player cannot deploy mission supports and cannot have a disguised agent. These missions are still doable, but the risk of running into enemies around a corner is greater.

INFORMANTS:

Suspicious activities can turn out to be beneficial. One of these benefits is the discovery of an informant. In this case, the informant takes a while to dig up information. The estimated time to the delivery of the information is shown to the player. In the meantime, the Beholders might try to assassinate the informant, though the player could stop this with a counter-operation.

DANGER LEVEL:

As mentioned earlier, the Cabal’s headquarters can be discovered and compromised. To represent this risk, there is the Danger level meter. A full meter raises the risk of the headquarters being raided, apparently by forces that are aligned to the Beholders or those that are their cat’s paws. The Danger meter only ever rises too.

The Danger meter would not change, if the Beholders are not carrying out operations against the Cabal and the player is not making decisions that would reveal the headquarters to outsiders. However, this is rarely the case.

One of the ways that the Danger meter would increase is the recruitment of new agents. Apparently, revealing the Cabal to potential recruits and having the recruits get their affairs in order before joining would increase Danger.

The Danger meter can rise slowly and steadily if the Beholders have a cell somewhere in the world. Cells can also reduce the income of the Cabal (presumably through leaning on anyone who is funding the Cabal). Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to locate cells as soon as possible. Conveniently, the presence of a slow but steady increase in Danger is an indicator that there are cells around.

The worst increases in Danger are those that are caused through the operations of Beholder agents. Indeed, the player deserves this setback, because these Beholder operations are among the easiest to disrupt due to the long time windows for the missions that can be carried out against them.

HIDEOUTS:

There is no way to reduce Danger, as the game would point out. The only way to keep the Cabal’s headquarters safe is to move it. This is easier said than done, because this costs money and will be the most common big expenditure throughout the playthrough. Furthermore, in order to move the headquarters, there must be hideout candidates available. These are found through intel rewards and investigations of suspicious activities.

The locations of the hideouts coincide with the locations of the cities, so some hideouts may be situated in cities that are far away from other cities. The cost of moving can also vary from hideout to hideout, with no clear observable pattern. The initial Danger level of the new headquarters also varies considerably, usually inversely proportional to the amount of money for moving.

Thus, the player would have to balance his/her choice between these factors. The new headquarters needs to have a low enough Danger level so that the player does not need to move it so soon again. It also needs to be close enough to other cities so that agents do not spend too much time travelling.

PROGRESSION OF TIME:

The in-game duration of a playthrough is numbered in hours and days. The timeline only ever progresses when the player is looking at the world map, which shows the abovementioned hide-outs, locations of agents, cities and missions. A rudimentary set of controls lets the player speed up or pause time. This is not unlike what has been done since the days of the first X-COM by (the now-defunct) MicroProse.

Interestingly, time does not progress when the player is carrying out missions, no matter how many turns that the player used.

STEALTH OR VIOLENCE, BUT NOT BOTH:

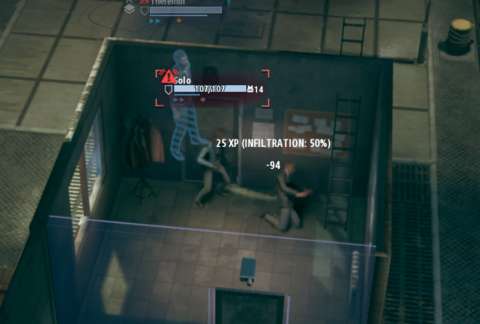

When the player initiates a mission that goes into tactical turn-based gameplay, the game switches to a 3D environment with grid-based layout. The player will be using this grid-based layout for both purposes of combat and stealth.

However, the game does not allow for both instances to run simultaneously. During a mission, the player either goes loud, or not all. If the player goes loud, there is no way to return to a stealthy solution for the mission.

Stealth is the default gameplay for most missions. The player is encouraged to have things stay that way due to the complications of going loud (which will be described later). This is unfortunate, because there are some interesting designs that make combat in Phantom Doctrine a tad different from those of other tactical turn-based games.

ACTION POINTS AND FIRE POINTS:

Like XCOM 2, Phantom Doctrine has a system that gives player characters “Action Points” (“AP”s) to use during their turns. In this game, Action Points are mainly spent on moving about. There are some other actions that use them, such as reloading large guns, firing guns in automatic and using certain items. Any APs that are not used at the end of the character’s turn are wasted.

Interestingly, there are also “Fire Points”. All attacks require Fire Points, one of which is given to any agent by default in his/her turn. Fire Points are also needed to use certain special abilities. Like Action Points, any unused Fire Points are wasted at the end of the turn.

The implementation of Fire Points does make the gameplay of Phantom Doctrine notably different from many other tactical turn-based games. In particular, firing different guns can require different amounts of Action Points, or none at all. For example, handguns only require Fire Points to be fired, so the player could use Action Points to move an agent closer before shooting them.

Generally, attacks end turns. Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to consider using Action Points to do something prior to that, like having agents get to a better location.

GOING STEALTH:

When the player’s team of agents is inserted into a mission area, they generally begin with quiet circumstances; this is called “Infiltration” in-game. The player’s agents always begin out of sight of enemies, although it is still possible to blow one’s cover right in the first turn due to really bad luck (more on this later).

The player’s choices for the agents’ body-wear is particularly important here. Having an agent go into a mission area with obvious body armour will immediately alarm any other person that saw the agent. (Indeed, if the player intends to play a mission completely in stealth, there is no reason to have any obvious body armour.)

The player’s agents can move about in the mission area in quite a number of ways, thanks to their general fitness. In particular, agents can fall down one floor without any problems, even so if they happen to be carrying anyone.

There are people that are already in the mission area. The type of locale that is the mission area determines their composition. For example, a large automobile garage has a mix of civilians, policemen, private security detail and enemy agents. A military base would have mostly soldiers, some support personnel and, of course, enemy agents.

These different characters have different behaviours, but there are always some similarities, especially outside of combat. For one, any of them will be alarmed if they saw the player’s agents in restricted areas, or spot any agent with body armour.

If they are not alarmed, each of them has a behavioural pattern that the player can easily observe. Any behavioural pattern that is not about standing where they are would typically involve moving to and fro along a set path, often within a single room. This is especially so for enemy agents.

There are some enemies that do have troublesome behaviour during Infiltration. The most notable of these is the Artemis Spook. It has considerable movement range. Its patrol route consists of at least two rooms, and might include the outdoors too.

SPLENDID CONVENIENCES:

One of the best designs of Phantom Doctrine is how the game automatically calculates the path of agents. All of the basics are shown to the player, such as the range of the agent’s movement and his/her exact path. By default, the game tries to avoid having agents cross into the vision of NPCs, especially in restricted areas (more on these later). The game shows how close they are to being spotted by NPCs.

Most importantly, the game will show the outcome of a move, specifically whether the alarm would be raised or not. Even if the player’s agent has not detected any NPCs that would give them away, this outcome will be visible to the player.

The visual display of the range of an agent’s movements generally omits seemingly empty squares that NPCs are actually occupying. This helps the player detect the presence of NPCs that can complicate the player’s plans.

NEAR--UNBELIEVABLE CONVENIENCES:

Phantom Doctrine’s developers pride themselves on insisting that the player could possibly carry out most missions completely in Infiltration. What they do not say as loudly is that they have implemented a lot of conveniences that make this possible. Some has already been mentioned, such as agents being able to fall one floor down from anywhere without any problem.

For one, the player can see the paths of any NPCs that his/her agents have spotted, including where they will end their turn. Their exact facing when they end their turn is not shown, but this should not be too difficult to ascertain as the facing of an NPC depends on his/her path.

The player can also see the hit points of spotted NPCs, though other information is not clear. Nevertheless, the information on hit points is the most important, due to a mechanism for takedowns that will be described later.

When a character moves through a door without opening it, the character will automatically open the door before going through and then close the door after doing so. Oddly though, if a character opens a door deliberately after stopping in front of or next to it, the door will not automatically close; the player needs to have a character deliberately close it. This is important to keep in mind, because open doors do not block line of sight.

UNBELIABLY SILLY CONVENIENCES:

Next, there are the game designs that result in unbelievable circumstances. Firstly, all NPCs are practically deaf to anything but gunfire, and they have narrow tunnel vision. Indeed, an agent could land next to them from an upper floor after crashing through a window, and they still would not notice it.

Speaking of windows, in XCOM 2, crashing through windows or doors will immediately trigger the alarm. This is not the case here. NPCs are deaf to the sounds of windows being broken, even if it happens in the same room. NPCs will also not notice broken windows.

These obvious gaps in the senses of NPCs have been deliberately put in place by the game designers. Apparently, they wanted to encourage the player to use different routes to get to the objectives in a mission, even at the cost of believability.

HIDING & DISPOSING BODIES:

However, any NPC will notice the presence of bodies, unconscious or dead. They will also notice any agent that is carrying a body. This NPC is guaranteed to raise the alarm as soon as he/she has spotted any of these circumstances. Therefore, the player has to be careful about when and where to knock out or eliminate NPCs.

If the player is sure that a body would not be found, the player could leave it where it is. For any other bodies, the player will need to move them out of the way or “dispose” of them.

Moving bodies out of the way burdens the agent and prevents them from doing much of anything else while carrying bodies. However, there are a number of missions that require the player to exfiltrate with an NPC, and there is an incentive to capture enemy agents later in the playthrough.

At any difficulty setting below the highest, the player has the option of having agents “dispose” bodies. After a brief animation of them picking up the body, the game fades to black and the body disappears. It is unbelievably convenient, but it is certainly much less troublesome than hiding the bodies. However, this consumes the agent’s Fire Point for that turn, which may prevent the agent from doing other things, like knocking out another NPC that would discover the body.

RESTRICTED AREAS:

The agents are not people who live or work in the mission locations, so if they are discovered in areas where they are not supposed to be, it would be obvious that they are intruders.

These areas have their borders delineated with warning symbols. They do not have bright contrast, but are noticeably animated. This helps in highlighting these areas without being too visually obtrusive. However, some restricted areas have objects along their edges and that can obscure the symbols, such as furniture, cabinets, washing sinks and other wall-mounted objects.

MOVING INTO RESTRICTED AREAS UNDETECTED:

Moving into restricted areas is a different matter than being spotted moving about in a restricted area.

An agent may be in the sight of an NPC when he/she moves into a restricted area. If the NPC can see the squares that the agent would move onto when he/she enters the area, the alarm goes off. The player is forewarned about this as long as the agent can see the NPC.

However, if the NPC could not see the agent moving on any square in the restricted area afterwards, it is alright. This even applies to cameras. This programming loophole can seem silly at times.

DIAGONAL MOVEMENT:

Square grids are common in video games, because of how simple they are to implement. However, movement across the grid is a contentious matter. For one, Japanese game developers only ever allow movement in the cardinal direction, which prevents any ambiguities but makes movement look especially artificial. Western developers often implement diagonal movement too, which while looking more believable, happens to cause some exploitable oddities.

The latter occurs in the case of Phantom Doctrine. It is possible for the player to have an agent snake a path through a tight “corridor” of squares that are not observed by NPCs. This corridor may include squares that are set diagonally from each other.

DISGUISES:

The hard counters to restricted areas are disguises, which are only available if the agents have done tactical recon of the mission location. As mentioned earlier, the agents do not live or work at the mission locations – but they can still infiltrate the local population to pass themselves off as people who belong.

Narrative-wise, it is not clear as to how they are able to reliably pass in their disguises. Most of them appear to be clothes meant for employees that should have access to every place in the mission location, such as janitors in office buildings and scientists in lab complexes; these are enough to pass cursory glances. Yet, some of these locations are strategically sensitive enough such that they should have stricter measures. Of course, one could argue that this is the late 1970s, and there has yet to be substantial advancements in security layers.

Anyway, disguised agents start missions well inside the map. This represents the opportunity that they have seized from the use of their disguise. The agents cannot carry anything other than small firearms. They lack any armor too, including concealable armor, so if things go loud, they are at a disadvantage.

CAMERAS:

Camera systems are already available in the late 1970s, though automation like facial and pattern recognition were in their infancies. This would not stop Phantom Doctrine from implementing unmanned security cameras that can automatically detect intruders.

In many mission locations, there are security cameras mounted at strategic locations, such as above doors and at the top of staircases. The procedural generation for maps often makes such placements.

These cameras practically act as disembodied NPCs that are always looking at a specific direction. They can be deactivated, but they cannot be permanently disabled and there are no means to neutralize them while they are activated.

Their sight range and cone of vision do not reach as far as those of NPCs, however. Therefore, it is possible to sneak around outside of their range, especially if the room that they are in is too big for complete coverage.

They are also subjected to the design loopholes for intruder detection that had been mentioned earlier. In particular, security cameras that are mounted above doors into restricted areas will never register the entry of any undisguised agents, as long as they are mounted outside the restricted areas.

All cameras can be deactivated, if the player can find the control console that is associated with them. The game does not indicate which camera belongs to which console, unfortunately.

TRIP LASERS:

Some restricted areas have defences in the form of trip lasers. These immediately trigger an alarm as soon as somebody passes through them, even if he/she has a disguise.

Even if the agent could not spot the trip lasers, the player still could. Trip lasers always appear together with emitter arrays, which are ever-visible. However, the player will need to rotate the camera around in order to spot them, because they only appear on one side of a door.

Of all the security measures in a mission location, the trip lasers tend to be the least believable, particularly if they have been procedurally generated. Trip lasers are intended to prevent access to places that no one should be in; in pre-designed levels, this is usually the case. However, the procedurally generated ones may have NPCs in the rooms behind the trip lasers.

Trip lasers have to be disabled from a console. This console looks notably different from the one that is used for security cameras.

LANGUAGES & DISTRACTION:

Some agents know more than one language (especially the main player character), but most know only one. Somehow, the Cabal and its management have no issues handling agents with different backgrounds and different lingual aptitudes. Therefore, the hour-to-hour running of the Cabal is not hampered by language barriers.

However, the language barriers do matter, even if a little, in the Infiltration phase of the mission. If the agent does not speak the language of the locals, he/she will not be able to verbally interact with them – which is perhaps just as well because they are supposed to keep a low profile.

On the other hand, talking to an NPC is an easy way to keep him/her distracted, and talking can only be done if the agent can speak the same language. During the preparations for a mission, the player is shown what language the locals speak and any matching languages that agents have would be highlighted. It could have been more convenient if the agents themselves have been highlighted, but this is not the case in the build of the game that I played.

Anyway, an agent who speak the same language can divert the attention of an NPC that is not a Beholder operative unto him/her. This causes them to turn away from where they were facing, which is likely what the player needs. The distracting agent does not end his/her turn, by the way, but doing anything like moving away will end the distraction. Thus, distractions are best used against NPCs that are able to see each other.

However, if the distracting agent is obviously in an alarming circumstance, e.g. in a restricted area, this distraction attempt backfires.

FOG OF WAR & SOME ODDITIES:

Even if the player has done tactical recon of a mission location, there will still be fog of war. This represents the limited senses of the agents. The range of the agents’ senses are not clear, however. The most that the player could discern from this is how much fog that they dispel.

Agents that are just at a corner will automatically look around the corner. They are given rather generous arcs of vision too, as if they are already standing around the corner.

Any NPC that is within the fog of war do not have their paths and cones of vision visible to the player, meaning that the next corner that an agent would take while in a restricted area might be spotted by an NPC.

However, there are still some oddities that an observant player might notice and make use of. For one, any square that is occupied by an NPC will not be shown as a viable spot to end a movement action in. This gives away the presence of these NPCs.

If an agent can interact with any object in the fog of war, the visual indicator for the projected outcome of the interaction also includes any forewarning about the alarm being raised. Of course, this would mean that unseen NPCs are observing that object in the current turn.

CAUSE OF ALARM:

There are many ways to trigger the alarm, and not knowing what triggered it can be frustrating. Thankfully, the game does show the cause for the raising of the alarm, albeit the player has to wait several seconds for the notification to appear, especially if the alarm was raised during the enemy’s turn.

Yet, there are missions in which the alarm would go off due to pre-determined scripts. Usually, the player is forewarned about this, but there are more than a few mandatory story-advancing missions that do not inform the player about this.

AGENT GEAR:

There is not a lot of gear that the agents can have, though each of them has the luxury of having two guns somewhere on his/her person. Certain situations like disguises would prevent them from packing anything but handguns and submachineguns, but even these can hurt a lot and they are easier to use than heavier guns anyway.

Each agent can obviously have only one set of armor. This can be a ballistic vest, worn under their regular clothing (all of which are sensible, by the way). Alternatively, the player could deck them out in full combat armour, which outright alarms any NPCs and weighs down the agents. Getting the agents around stealthily will be a pain, but many mission locations are mostly composed of restricted areas such that this is sometimes not an issue.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there are the two tools that an agent can carry. These can be grenades, useful for when enemies are behind thick cover or have made the (rare) mistake of bunching up. There are several types of grenades too, including gas grenades that are practically area denial weapons. There can also be mines, which are useful in tight places.

NOT A LOT OF TOOLS FOR STEALTH:

There could have been some tribute to the James Bond IP, specifically the presence of gadgets that help a spy get through places. This is not the case for Phantom Doctrine.

For much of the playthrough, the only tool that agents can reliably use during Infiltration is the lock-pick. Late into the game, there are “noiseless” mines too, which can kill without raising any alarm, but the player might be better off having a pair of agents stalk and take down a target.

Most other tools will trigger alarms when used. At least this warning is shown to the player.

DOORS WITH IMPOSSIBLE LOCKS:

An observant player might notice that some doors are marked with symbols of red padlocks. These are doors that can never be opened. In the procedurally generated maps, these appear whenever the game makes the mistake of putting a door next to the boundaries of the mission location.

In special missions, these are practically progress gates that cordon off other areas of the map until the player achieves some objective. They are also used as “monster closets”, to use a term that describes any off-limits feature of a map that is used to spawn enemies. These designs can damage the believability of the game.

CANNOT CHANGE GEAR DURING MISSIONS:

Whatever gear that an agent is equipped with will be all that he/she has during a mission. There is no way to change gear, even if the agent comes across gear from loot containers during a mission.

Of course, this follows the trend that the XCOM reboots have set. However, they have the excuse of urgency. In Phantom Doctrine, the Infiltration phase could have given enough opportunity for the agents to slip into some other gear. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

TAKEDOWNS:

One enduring trope in super-spy fiction is how spies seem to be able to knock out unsuspecting people with a single blow. This trope is present in Phantom Doctrine.

The gameplay mechanism for the takedown depends on only one factor: the hitpoints of the aggressor and the target. Specifically, the aggressor must have higher max hitpoints than the target. This means that most unnamed enemies are vulnerable to the player’s agents, who often have more hitpoints than they do, whereas named enemies – who are Beholder operatives – are less vulnerable.

Obviously, performing a takedown on an NPC that the others can see will immediately trigger the alarm. If the player’s agent can see the other NPCs that can see the intended target, the player is forewarned about this through visual indicators.

Takedowns can be performed in combat too. Indeed, it might be prudent to use takedowns, especially if the target has too much Awareness (more on this later).

Due to the need to have more hitpoints than the target, most players would focus the development of their agents around their hitpoint amounts. This is just as well, because agents with more hitpoints obviously last longer if and when combat occurs.

Very late into a playthrough, the game introduces enemies that are immune to takedowns. If the player has the foresight to have them, silenced/suppressed guns are good substitutes to takedowns.

ADJACENCY DETECTION:

Most of the capabilities that NPCs have in discovering the player’s agents are informed to the player. However, one of them is not well-communicated.

This is the ability of any NPC to register the presence of the player’s agents at the start of his/her turn, if the player’s agents are in an adjacent square. This square can be either in the cardinal or diagonal direction, and it does not have to be in the NPC’s vision arc.

If the player’s agent is not doing anything overtly alarming, then he/she is safe. Otherwise, if any of the above conditions are not fulfilled, the alarm is raised immediately. Learning this the hard way can be unpleasant.

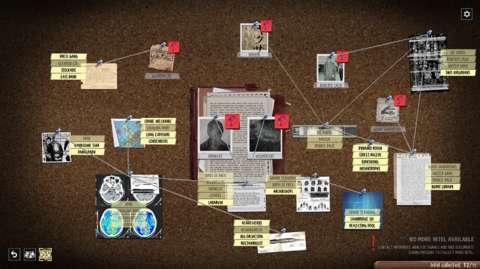

INTEL:

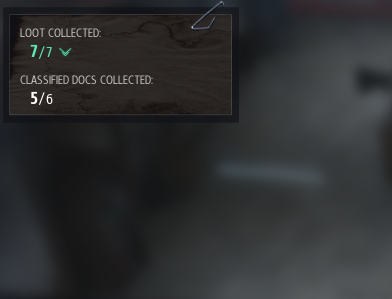

Throughout mission locations, there are documents that the agents can take photos of. Presumably, these are documents that the resident Beholder operative(s) has (rather carelessly) left around. These are practically the tertiary objectives of the missions, because these documents contain information that the player needs in order to progress in Investigations (more on these later).

The player would know that an object is a piece of intel if it is shining and having other visual effects that make it stand out. If the player has done tactical recon, the player can see the locations of all pieces of intel.

Gathering intel will immediately alarm any NPC that happens to see it happening. For this reason, many of them are often watched over by at least one NPC, and at least one piece of intel is within one turn’s movement of a Beholder operative.

LOOT:

There are also gear cabinets and lockers that the agents can break into and steal things from. Like intel, loot containers have different visual effects, which is just as well because the game uses the models for regular furniture.

Strangely, loot does not include any money that can be stolen from the premises.

ENEMY AGENTS IN MISSION LOCATIONS:

Any mission location will have at least one enemy agent. There are very few exceptions. This enemy agent can be an existing one, in which case his/her statistics will be updated so that he/she would be of some challenge. If there are no extant enemy agents or not enough of them to meet the minimum level of challenge for a mission, the game simply spawns new ones.

These Beholder agents are always disguised as civilians, so they will never sport any body armour. They may even have awkward appearances, such as sporting a ten-gallon hat in Hong Kong. Still, they always (somehow) fit into the mission location.

Beholder operatives are always revealed as such whenever they are spotted. Their civilian guise might require a second look at any seemingly civilian NPC, but more often than not, their clothes make them seem out of place, e.g. having a burgundy jacket that just stands out in a military base.

While things are still quiet and the player’s agents remain undetected, the enemy operatives go about on their pre-determined patrol paths. The player can also see their patrol paths, if his/her agents have spotted them and they are not yet vigilant (more on this later).

If combat breaks out, the enemy agents are always somehow aligned with the local security and law enforcement (if any). It is unclear how they manage to secure the allegiance of the unnamed mooks, but there is the hand-wave excuse that the Beholders have considerable influence.

The main risk that Beholder operatives pose is their considerably long line of sight. This is often counter-balanced by a narrowed cone of vision, which can seem silly at times. However, some operatives do have perks that widen their cone, making it impossible to sneak up to them from anywhere but their rear arcs.

Any of the player’s agents that cross into their line of sight will be spotted immediately, and the alarm raised. This also includes any agents in disguise.

VIGILANCE OF BEHOLDER OPERATIVES:

Beholder operatives become more suspicious if the player has been knocking out people. The game describes them as having noticed that guards had been absent from their usual patrol routes, but in truth, this is a flimsy disguise for a script that automatically triggers when too many NPCs had been taken down stealthily. Besides, the counter for that script trigger also includes civilians.

Anyway, Beholder operatives that have turned vigilant will drop their usual patrol routines. Their paths are no longer noticeable to any of the player’s agents that have spotted them. They also make a beeline towards any security console, intel items and loot containers.

In the case of the security consoles, the operatives turn them back on if they had been turned off. In the case of intel items and loot containers, the operatives somehow make them disappear and irretrievable.

This is an interesting way of discouraging players from simply knocking out NPCs willy-nilly in missions, and also a way to encourage them to consider the paths that their agents take.

GOING LOUD:

If the alarm is raised, every agent takes their weapons out from somewhere on their person, regardless of how ludicrously large it is. Anyway, the agents must shoot their way out. This is easier said than done, because all enemies know the exact locations of the player’s agents. All of them – law enforcement, private security, gangsters and enemy operatives – will work together.

Combat would use most of the gameplay systems that the infiltration gameplay would use, such as Action Points and Fire Points. Like the actions that the player’s agents can perform during Infiltration, combat actions come with descriptions that describe their costs and consequences, such as whether an action ends a turn or not.

Every character has unlimited ammunition supplies, not unlike the XCOM reboot. However, all guns have magazines with limited capacities, and most guns other than revolvers have different fire options that consume different amounts of ammo.

DISCOURAGING COMBAT:

Despite its designs for combat, it would soon become clear that the developers do not consider combat to be the main part of the gameplay. The expression of this is the ceaseless and increasingly nastier enemy reinforcements that would be coming in from certain edges of the map. Therefore, the player must achieve the mission objectives as soon as possible, because his/her team will eventually be overwhelmed by the reinforcements.

Still, despite the gameplay’s obvious emphasis on keeping stealthy, there are enough competently-done designs that make combat quite a joy.

NO CHANCE TO HIT:

Ever since the debut of the XCOM reboot, there had been grumblings that the use of percentage-based probabilities for combat purposes is an infuriatingly and frustratingly dissatisfying gameplay mechanism. There have been attempts to move away from this and implement more deterministic mechanisms in their place. Phantom Doctrine is one such attempt.

All attacks made by any character is guaranteed to do something detrimental to the target. In the case of attacks made by the player’s agents, many of the factors that determine their effectiveness is within the control of the player, or at least observable.

Of course, there are concerns that without elements of luck, combat would just turn into a drawn-out game of chess, where the winner can already be determined in the opening moves. This is where the various factors of combat introduce complexities in the flow of battle.

AWARENESS:

Awareness is a statistic that is practically the combination of an “energy” meter and a “shield” meter. Only Cabal agents, Beholder operatives and professional soldiers have Awareness. Most mooks, such as law enforcement officers, do not have them.

Awareness reduces incoming damage, as long as the character has enough Awareness to absorb the reduction that would be incurred. This represents the effort that the agent is spending on not getting shot.

The reduced amount of damage is shown to the player, but the extent of this damage reduction due to Awareness aside from other factors is unclear.

Any damage that is mitigated by Awareness will be applied as a reduction of Awareness. Therefore, if there is not enough Awareness to absorb this reduction, the character would take most of the damage from the landed hit.

Indeed, one of the ways to defeat an enemy operative is to attack them repeatedly with small attacks in order to deplete their Awareness. Afterwards, attacking them with high-damage guns would finish them off quite efficiently.

During Infiltration, only Beholder operatives have Awareness, though they do not start with a full meter. This represents their near-paranoid vigilance. This means that it is not possible to gun down Beholder operatives with silenced/suppressed weapons, at least not without special abilities that bypass their Awareness.

SPENDING AWARENESS:

In addition to being spent on reducing incoming damage, Awareness can be spent on activating certain abilities. These abilities are generally those that the Agent’s training grants. For example, there is Exertion, which increases the movement distance of the agent while consuming some Awareness.

Such expenditure represents the effort and attention that the agent is investing into the move. Therefore, it is understandable that their reduced Awareness makes them more vulnerable to incoming attacks.

In addition to Fire Points and Action Points, the firing modes of some guns consume Awareness too. This is especially so for light machineguns. Therefore, the player has to be careful when to use them, lest the agents do not have enough Awareness to absorb the enemy’s attacks in their turn. Indeed, combat would become a matter of managing Awareness levels.

WEAPON PROFICIENCIES:

There are many guns, but perusing them is not a simple matter of equipping agents with guns that have the biggest statistics at the time. Of course, the player could still do this, because there are indeed guns that are straight upgrades above the rest. However, whether the agent could eke the most out of his/her gun depends on his/her proficiency with it, or lack of it.

Any training module that an agent has will give him/her proficiencies in at least two weapons. Different modules give different proficiencies; there does not appear to be any overlaps.

Having proficiency in a gun makes the agent more efficient in its use, such as using less Awareness. However, the main and most obvious benefit is the ability to trick out the gun with mods.

GUN MODS:

Gun mods are mainly how early-game weapons can be a bit competitive with the ones that appear later. Incidentally, the ones that appear later have fewer slots for mods, presumably due to their more complicated engineering.

Anyway, these mods do things that experienced players would not be surprised about. They add damage and improve armor penetration, to cite some examples. Some mods have give-and-take effects, such as increasing armor penetration in return for reduced damage.

The most important gun mods are silencers and suppressors. Silencers for handguns can mitigate noise without any damage reduction, whereas suppressors for submachineguns and rifles mitigate noise in return for some loss of damage. The damage reduction, if any, is a small matter, if the player’s intention is for these weapons to be usable during the Infiltration phase.

Indeed, an agent with a noise-suppressed high-powered sniper rifle can be incredibly helpful in eliminating a target where two agents in close proximity might not be feasible.

COVER:

Cover reduces the amount of damage from incoming attacks. There are two grades of cover: low cover, which is usually waist-high obstacles, and full cover, which is usually a wall or a large vehicle.

How much damage is reduced is not entirely clear. However, full cover is generally better than low cover at reducing damage.

Interestingly, cover does affect area-of-effect attacks. For example, a telephone booth prevents a grenade from hurting a character that happens to be on the other side of the booth.

SOME DESTRUCTIBLE ENVIRONMENT:

Buildings generally cannot be destroyed. Specifically, their walls and floors are indestructible. However, the other things can be thrashed. Windows and doors can be ripped apart from stray gunfire, however. Indeed, characters would eagerly smash intact windows in order to be able to shoot through them.

Some pieces of cover that are not part of walls cannot be destroyed. This includes concrete blocks and pillars. However, some others can be destroyed. For example, railings along walkways can be shot apart. The player is not shown the durability of the destructible cover pieces that is being damaged, however, so it is not clear whether these have hit point meters or their destruction is randomized.

GRENADES:

Grenades are powerful tools, but obviously each can only be used once. Although grenades are substantially affected by cover, they bypass any protection from Awareness. Indeed, grenades are very effective at eliminating Beholder operatives, if the player could not have his/her agents do takedowns on them.

Grenades in Phantom Doctrine do not destroy the environment as readily as those in XCOM 2. Therefore, the player should not consider using explosives to make new entrances into someplace, because this is not that kind of game.

BREACHES:

Sometimes, NPCs might be in a room facing each other, and that room is a restricted area. Therefore, there is no way to sneak up on them.

There may be an enemy agent that has just too many hit points for a takedown, and too many for any silenced or suppressed gun.

For such situations, there is the option of performing a breaching. Breaching lets multiple agents attack near simultaneously, with the outcome of the breaching attempt only resolved after all of them have made their attacks.

There is a major condition that has to be fulfilled before breaches can be used. Firstly, the room has to be fully enclosed and it must of course be indoors. Presumably, the coding for the breaching manoeuvre depends on these conditions.

To perform a breaching, at least two agents must be just outside the room, in front of one of its entrances. If the room fulfils the abovementioned condition, the player can pick which agents get to participate in the breach, as well as the guns that they would use. Having more participants increases the damage output of the breaching attempt.

Upon commencing of the breach, the agents enter the room shooting at anyone in it that they can draw a line of fire to. The detection scripts of NPCs are suppressed during a breaching attempt, so any agent can enter through any entrance without triggering the alarm.

If there are multiple targets that any of the agents can see, the player can assign a priority target to each agent. Of course, enemy operatives should be priority targets, whenever possible.

FAILING A BREACH:

A breach with guns that are not silenced or suppressed will automatically trigger the alarm, regardless of the outcome. The alarm will also definitely be raised if there are any survivors that had been shot in the breaching attempt.

After the breaching attempt has ended, the agents will be in the room standing at spots that had been pre-determined earlier. The detection scripts of NPCs are also restored. If there are still NPCs in the room and they had not been shot, the alarm would not be raised as long as they cannot see the agents. If they do, then of course the alarm goes off.

PROBLEMS ABOUT BREACHING:

Despite the prior statement that more agents means more damage from a breaching attempt, the player is not shown the amount of damage that the agents would do before the breaching attempt. The player would have learn about this through observation by trial-and-error.

Generally, anything that is not a sniper rifle can be fired twice. Indeed, sniper rifles are terrible for breaching. However, neither information is told to the player.

The agents go into the room at their own pace, shooting at their prioritized targets first. Yet, breaches could have been more sophisticated and controllable if the player can control their sequence of shots.

MOOKS:

As mentioned earlier, most mooks do not have Awareness meters. Therefore, when they are hit, they can only count on their armor to reduce damage.

Mooks that do have Awareness do not begin combat with any. In fact, during Infiltration, their Awareness regeneration is suppressed, meaning that it is possible to kill them outright with silenced/suppressed weapons. Furthermore, mooks have noticeably less hit points than Beholder operatives, and their hit point meters are more consistent than the operatives’ too.

Indeed, during combat, if the player’s agents could get decent enough cover and the mooks could not, the player’s agents would be eliminating them rather handily.

REINFORCEMENTS:

Mooks do have one advantage, however: they will keep on coming, no matter how many that the player kills. Fresh squads of mixed mook types appear from the edges of the map, especially the ones that are connected to roads or obvious points of entry, such as elevators.

Generally, these fresh mooks do not appear close to the evacuation zones. However, some maps have edges that could not accommodate the arrival of reinforcements, such as the naval port in which a special mission takes place. In these cases, the evacuation zones would be uncomfortably close to where the fresh mooks would appear.

Ostensibly, the player could attempt to farm XP by killing the reinforcements. However, there are some designs that have been put in place to discourage this. Chief of these is the escalating response; the reinforcements are bigger and come more frequently.

CRUTCHES FOR UNWISE DECISIONS:

Ultimately, the player’s main method of defeating enemies when things go loud is to exploit their poor decisions, specifically how they approach the player’s agents.

Generally, all enemies will attempt to get closer to the player’s agents so that they can shoot at them. This is understandable, but if the player can foresee their avenues of approach, the player can have them cut down with overwatch fire.

They do exhibit some attempt at strategy, such as fanning out so that they can attack the player’s agents from different directions. However, they are not good at timing their attacks, so they have a tendency to come over piece-meal.

The main advantage that enemies have is that they always know where the player’s agents are. Considering the fog-of-war in most maps and how many things can block line of sight, there are many chances for them to attack from angles that the player’s agents could not cover.

Both designs have ever been tropes in games with tactical turn-based gameplay and fog-of-war. It is unfortunate that Phantom Doctrine does not buck the trend, though its lesser dependence on factors of luck gives more certainty to combat encounters.

FULL XP GAIN FOR COMBAT:

When the player takes down an enemy during Infiltration, that enemy yields experience points just like he/she would if he/she is taken down in combat. However, the gains are halved.

This is a peculiar gameplay design, and would especially seem so for players that have the notion that stealth is more challenging than combat in video games.

Yet, combat is actually more difficult in Phantom Doctrine. This is due to unending reinforcements and the fog-of-war that can cover the approach of incoming enemies that know exactly where the player’s agents are.

Therefore, the full gain of experience points from combat is likely a compensatory design. Yet, it might not be in the player’s interest to make use of this, due to the risks involved.

CIVILIAN LOSSES:

There are always civilians at mission locations. During Infiltration, they mill about, doing scripted routines. During combat, they freak out, assuming cowering positions and trying to stay away from combatants on either side. Indeed, if a combatant from either side gets near them, the civilians appear to obtain a “free” turn to move away.

This is just as well, because having a civilian get in the way can be frustrating. It is also entertaining in a macabre way; “bouncing” a civilian from one spot to the next by moving agents near them is hilarious.

It is not possible to hit a civilian with stray fire during combat, because there does not appear to be any scripts to have stray fire hit characters other than the intended targets. It is possible to kill them with grenades, but due to their tendency to run away, it is unlikely that they would be caught in the blasts.

Indeed, civilian casualties are much more likely to happen during Infiltration. Ideally, the player should use takedowns on them, but the player might want to have more expedient means of preventing them from raising the alarm. Civilians die outright when hit with any gun, by the way.

Civilians that died will increase danger levels significantly, representing the uproar over the deaths of by-standers. This can seem amusingly odd, because there are no increases in danger for killing dozens of law enforcement officers, private security or soldiers.

STABILIZING AGENTS:

Agents and Beholder operatives may be individuals that have been subjected to a lot of indoctrination, but that was possible because they had strong will in the first place. This also means that they are innate survivors.

Gameplay-wise, agents and Beholder operatives do not always outright die when their hit point meter reaches zero. They will take a few turns to die. This process can be stalled by carrying them around; carrying them somehow causes the countdown to freeze.

Having an agent carry them around can be difficult, because this agent can do little else. Therefore, a better solution is to “stabilize” them, which removes the countdown. Conveniently, every agent has chemical syringes on his/her person that can somehow do so rather reliably.

However, the amount of APs that are needed to perform the stabilization can vary. If more turns have elapsed since the agent/operative went down, more APs will be needed. If there is not any agent that can ever have enough APs, the downed agent/operative is doomed, unless someone carries him/her for the rest of the mission. The stabilization process also needs a Fire Point.

Strangely though, enemy operatives that have been incapacitated with takedowns are considered to be dying anyway.

Agents and operatives that are killed with grenades are often outright killed. They can also die if they are taken down with powerful weapons, such as sniper rifles.

EVACUATION:

Like XCOM 2, the player must have his/her underlings exit the mission location to get them to go home safely.

To do so, the player has to designate an evacuation zone. Incidentally, the player’s options in setting up the zone happen to be close to the insertion zones that the player did not pick before the start of the mission. Thus, the player could plan the routes to the objectives and to the evacuation zones prior to the start of the mission.

Any agent that is on the evacuation zone when the player issues the order to evacuate gets to go home. If an agent happens to be carrying another unconscious agent or enemy operative, both of them arrive at the headquarters. Any agent or enemy operative that is not in the zone is left behind.

Any agents that are left behind will raise the danger level for the headquarters. Presumably, their attempts to return is fraught with peril to the Cabal’s secrecy. Still, these agents have a chance of coming back home, especially if they had been left behind while the alarm has not been raised. (On the other hand, if things are still quiet, the player could have waited for all of the agents to arrive at the evacuation zone.)

If the agents had been left behind when the alarm has been raised, there is a likelihood of the agent being captured. The player may not see them again – likely not if the player has yet to earn their loyalty. They may also return as Beholder operatives, thus reminding the player of the Beholder Initiative’s insidious ways. Alternatively, they may return to the Cabal – but with a few extra Hidden Talents, one of which might make them a double agent.

MISSION XP GAINS:

Any agents that survive a successful mission gain additional XP. The amount that is awarded depends on how far the player has progressed in the playthrough. This has been implemented so that the agents can be developed such that they are competitive with the enemies that would appear later.

The gains are actually awarded as lump amounts. They are divvied equally among the survivors, regardless of how much that they have been doing throughout the mission. Therefore, it may be tempting to have fewer agents in misisons, if only to accelerate their development.

AMBUSHES:

For better or worse, there are some factors that are out of the player’s control when it comes to handling missions. The player could make all the necessary preparations to mitigate risk, but there are still conditions that the player could do nothing about.

An ambush can happen when agents go on a mission. This ambush can inflict injuries on the agents, kill them or cause them to be captured. The most troublesome of these is that the mission leads to tactical combat outright, thus risking all of the agents that went on the mission.

An ambush usually happens if any of the player’s agents have built up too much “heat” (more on this later). However, it can also happen if the game has reached a point in the story where an attack has to happen, if only to highlight the perils of having angered a collective as powerful as the Beholders.

This can be unpleasant, especially if the player has prepared the agents for Infiltration instead of tactical combat. Of course, one could argue that ambushes were meant to surprise the player, but not being able to reconfigure the gear of agents to fit the upcoming situation can be irksome.

COMPROMISED CIRCUMSTANCES:

In addition to ambushes, there are missions that would insert the player’s agents in an already precarious situation.

Chief of these are missions that are about eliminating a single enemy operative that has been carrying out a task that would endanger the Cabal. In these missions, the player is forewarned that the player’s agents have already been somehow “compromised”, and a response is coming in the form of the alarm being raised within several turns.

Of course, there is only ever just one Beholder operative, and his/her location is always shown on the map. Indeed, a disguised agent in these missions can reach the target in just two turns. However, the alarm being raised would make extrication rather unpleasant.

The writers could not even come up with a proper reason for the alarm automatically going off; the cause of the alarm is “force majeure”, specifically the “chance occurrence” interpretation of this Latin phrase.

SUPPORT ROLES:

In addition to the handful of agents that the player would be bringing into the mission, the player can assign several others into support roles. To do so, the player needs to have tactical recon performed at the mission location.

The support agents are presumably close to the mission location, specifically in buildings towards the cardinal directions. The player gets to set which cardinal facing that they would be located at before the beginning of the mission, so the player might want to survey the map prior to making those decisions.

The support roles that the agents get depend on the equipment that they have been given; the player must have enough equipment to get the support roles that he/she wants for the mission. This equipment can be crafted at the workshop, or purchased through black market contacts. The latter option can only ever be performed during mission preparation.